-

The Resurrection of Trump’s Support for Pete Hegseth - 26 mins ago

-

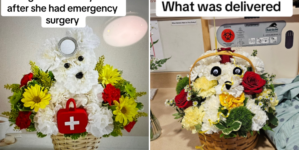

Woman Orders Flowers for Sister in Hospital—Hysterics Over What Arrives - 33 mins ago

-

Winds drop, chance of rain as fire danger ebbs in Los Angeles - 39 mins ago

-

Should You Vacation in South Korea? Experts Weigh In Amid Political Unrest - about 1 hour ago

-

Man Found in Syria Appears to Be Missing American - about 1 hour ago

-

Official says L.A. County may defy state order to close juvenile hall - about 1 hour ago

-

Will Joe Biden Pardon Hillary Clinton? Bill Clinton Weighs in - 2 hours ago

-

Can Psychedelics Help CEOs Boost Their Leadership Skills? - 2 hours ago

-

The UnitedHealthcare killing won’t improve insurance. This would - 2 hours ago

-

Kadyrov Troops Hurt as Drones Strike Military Barracks Deep Inside Russia - 2 hours ago

In three months, 26 foods have been recalled. Why you shouldn’t worry

Consumers in California were bombarded last month with 11 food recall notices that included raw milk from Fresno infected with H5N1 bird flu, organic carrots from City of Commerce contaminated with E. coli and cucumbers from Arizona that contained salmonella.

The notices brought the total number of recalled foods between September and November to 26.

It is normal to have this many recalled foods?

Experts say it’s hard to define what is a normal amount of recall notices and detected foodborne illnesses because the testing systems and investigative steps have significantly changed over time.

“Baby carrots [for example] could have been contaminated before but it could have gone undetected,” said Barbara Kowalcyk, director of the Institute for Food Safety and Nutrition Security at George Washington University.

In recent years, she said, there has been more invested in testing, investigation, identification and tracking systems when it comes to food safety, but it’s far from being a perfect system.

“As we get better at identifying, monitoring and tracking [contaminated foods] we will naturally see an increase in recalls because we’re just getting better at figuring stuff out,” said Sara Bratager, Senior Food Safety Specialist for the Institute of Food Technologies.

Though 26 recall notices in three months might seem like a large number, Bratager said it’s not unprecedented.

Trace One, a product management software company, studied the number of food recalls in the U.S. between 2020 and 2024 and found that the number of recalls grew from 454 to 547 per year. The leading cause of food recalls are bacteria, foreign objects and allergens that are triggered when products are exposed to wheat, dairy and nuts, often due to cross contamination.

California has the highest percentage of recall notices in the U.S. with 39.8%, followed by New York with 36.4%. According to Trace One, California has the largest share of recalls because it’s the nation’s largest producer of food.

Experts say the overall number of recalled food products has grown across the country because the food chain has become more complex as food is often grown, manufactured, packed and distributed by separate companies, which leads to more places in the supply chain where contamination can occur.

Any number of recalls feels significant but experts say recalls aren’t all doom and gloom: Outbreaks from contaminated foods are growing smaller, and there are several actions consumers can take to protect themselves.

Are recalls just bad news?

A recall means the production of a specific food is halted (sometimes voluntarily by the producer), the item is taken off the shelves and consumers are warned against eating or drinking the product because the food can cause injury or illness.

Foods can be recalled because they’re contaminated with bacteria, viruses or parasites, there’s a presence of foreign objects (broken glass, metal or plastic) or a failure to list a major allergen in the food packaging (such as peanuts or shellfish), according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

Recall notices have both a negative and positive association, said Bratager.

It’s bad because it means the preventive measures that are in place by the FDA and the U.S. Departmen of Agriculture (which regulates meat, poultry, and processed egg products) failed and contamination got into the food production process, Bratager said.

Recalls are also good because they signify that the process of investigation, identifying and tracking contaminated foods to alert producers and consumers is working.

“It’s a comfort and a scare because we don’t want to see recalls happening,” she said. “But at the same time I would be worried if I was living in a community where there was not a single recall.”

The number of infected in a recall is getting smaller, why?

On Nov. 18 the Los Angeles County Public Health Department alerted consumers of two local cases of E. coli associated with a multistate outbreak linked to whole bagged and baby carrots from a farm in Bakersfield.

In the county, one local case was linked to the outbreak and resulted in the death of an adult over the age of 65 with medical conditions.

It’s becoming more common to see recall notices and public health alerts that affect a smaller number of people who have become ill or died from contaminated food.

No recall is a positive event, Bratager said, but when a recall has a smaller number of people affected by the outbreak, it’s reflective of monitoring and detection efforts becoming more precise.

“Oftentimes the reason a recall is really big is because we find an issue and we can’t necessarily pin down when that issue happened and get to the root cause of it,” she said.

What can consumers do to protect themselves?

Before handling and cooking any type of food, Kowalcyk said, make sure you wash your hands with soap for 20 seconds. Secondly, ensure that the utensils and the surface area you’re using to prepare the food are sanitary.

When it comes to produce, make sure you’re washing it before preparing and eating. Soap isn’t necessary, said Kowalcyk. What’s more important to getting rid of bacteria on the food item is friction under running water and then using a paper towel to dry it.

Another rule of thumb is to keep raw meat and poultry away from other foods to minimize cross contamination.

Cook foods to proper temperatures by using a cooking thermometer, especially when cooking meats. For a complete list of safe minimum internal temperatures for various foods, visit the online USDA list.

“I know it’s fun, especially on holidays, to keep food out [to graze on] for a few hours, but you really don’t want [food] out for more than two hours, said Bratager.

Such proactive steps should extend beyond your own kitchen, said Darin Detwiler, a food safety expert and professor of food regulatory affairs at Northeastern University.

If you are dining at a restaurant, for example, Detwiler said, you should speak up if you see a staff member handling food who isn’t being hygenic, such as handling food with bare hands or not washing their hands. If your meal isn’t cooked properly, say the meat on your plate is raw, alert the staff.

What is a consumer’s roll in recalls?

If you get sick and you suspect the cause is a foodborne illness, experts say you should first consult your healthcare provider and then report it.

You can report a complaint of illness or serious allergic reaction to the proper regulatory system for the particular food item.

Issues with dairy products, produce, nuts, spices, and bottled water can be made online via the FDA’s Safety Reporting Portal or by calling (888) 723-3366 Monday through Friday from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Eastern time (the phone line is closed Thursdays and federal holidays).

Reports of issues with seafood should be emailed to seafood.illness@fda.hhs.gov with the following information: species of fish/fish products, location of illness, identify whether there are any remnants of the possible contaminated food, how many people have fallen sick and where the food was purchased.

Problems with meat and poultry should be reported to the USDA by calling (833) 674-6854 or by email to the meat and poultry hotline MPHotline.fsis@usda.gov.

Source link