-

Mark Zuckerberg’s Meta Donates $1 Million to Trump’s Inaugural Fund - 23 mins ago

-

Today’s ‘Wordle’ #1,272 Answers, Hints and Clues for Thursday, December 12 - 27 mins ago

-

Nike and NFL Aim to Boost Global Reach with Decade-Long Collaboration - about 1 hour ago

-

In Aleppo, Jubilant Syrians Return to a Ravaged City and Toppled Monuments - about 1 hour ago

-

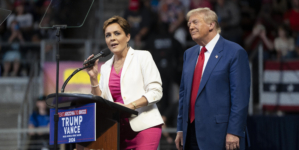

Donald Trump Announces New Role for Kari Lake - 2 hours ago

-

Dean of Students at Massachusetts School Charged With Conspiring to Traffic Cocaine - 2 hours ago

-

Outgoing House Republican: ‘The Less’ Congress Does, ‘The Better’ - 2 hours ago

-

Syria’s New Leaders Balance Huge Struggles Amid Disorder - 3 hours ago

-

Back-to-Back Bomb Cyclones Could Hit US - 3 hours ago

-

South Korea President Yoon Defends Martial Law Decree in Defiant Speech - 3 hours ago

Why California’s Latino voters are shifting toward Trump

Thirty years ago this fall, California’s Latino voters coalesced into a multigenerational ethnic voting bloc for the first time in response to a draconian, citizen-led initiative targeting immigrants who were in the state illegally. Proposition 187 sought to deny most of the state’s taxpayer-funded services to undocumented immigrants. While it was ultimately ruled unconstitutional, the proposition catalyzed a generation of Latino voters and politicians into a movement, binding the Latino electorate to the immigrant experience and shaping the state’s politics accordingly for decades.

A lot can change in 30 years. The emergence of a new generation of voters has combined with shifting attitudes about identity and security to upend those notions of what motivates the Latino electorate.

The reverberations of Proposition 187 established certain perceptions, both real and mistaken, about the nation’s fastest-growing voter group. Foremost among the misconceptions was the belief that immigration would be the primary lens through which Latinos would always see the world.

So what’s different today? Latino voters themselves are. They are rapidly ceasing to be any kind of cohesive ethnic constituency and becoming more defined as economically populist voters.

As Times columnist Gustavo Arellano has pointed out, “23% of Latinos and 63% of whites voted for Proposition 187, while a UC Berkeley Institute of Governmental Studies poll co-sponsored by The Times this year found that 63% of Latinos in California consider undocumented immigrants to be a ‘burden,’ compared with 79% of whites.” In other words, California’s Latino voters are now just as likely to see undocumented immigrants as a burden as the state’s white voters were in 1994.

Another poll, conducted by Mason-Dixon Polling & Strategy and Telemundo just weeks before the election, found that 70% of California Latinos believe illegal immigration is a somewhat or very serious problem.

The salience of Proposition 187 for Latinos is finally fading. The economic populism and assimilation of younger, U.S.-born Latino voters is overwhelming the concerns of naturalized immigrant voters. Nearly a third of Latinos who are eligible to vote are under the age of 30, according to the Pew Research Center, which means they weren’t even alive when Proposition 187 passed. And that doesn’t include many voters who are over 30 but still too young to have any formative political memory of that campaign.

But old memories die hard for politicians. To this day, many Democrats retain an obsessive focus on issues specific to the concerns of the undocumented even though the overwhelming majority of Latino voters are both U.S.-born and exasperated with the failure to address their economic plight, including the exploding cost of living and diminishing quality of life. While every credible poll of California’s Latino voters over the past 30 years has shown that the economy was their top priority, policymakers have yet to propose a comprehensive agenda specific to the most basic economic challenges facing Latinos.

Moreover, a shocking number of indicators suggest life in California has grown considerably harder for the Latino working class since the mid-1990s even as Latino representation has proliferated at every level of government.

The state’s dire housing crisis affects Latinos more than any other group. Latinos struggle to obtain science and technology degrees from our public universities even though high tech is the homegrown industry providing most of the state’s livable wages. Latino students entering California community colleges are more likely to be placed in remedial courses. Latinos are more likely to do gig work and less likely to be in unions. And nearly 60% of the state’s Latino children are covered by Medi-Cal, the state’s Medicaid program — shameful evidence of deeply entrenched poverty within the richest state in the union.

A survey I conducted with David Binder Research after the November election found that an astounding 90% of the state’s Latinos cited “The price we pay for everything” as their most important issue — outpacing concerns about homelessness, immigration, crime and even jobs. Affordability has become the primary concern of the Latino middle class.

While California Latinos have essentially been clamoring for the equivalent of a Marshall Plan to build the economy for the state’s largest ethnic group, the political overemphasis on those here illegally continues unabated. This year, legislation to provide housing down payment assistance to undocumented residents made it to the governor’s desk, where it was promptly and responsibly vetoed. And in Santa Ana, which is home to one of the largest Latino populations in California, residents resoundingly rejected a ballot measure that would have given undocumented people the right to vote in municipal elections.

Meanwhile, low voter participation and civic engagement among U.S. citizen Latinos is partly a consequence of persistent poverty, lack of homeownership and lower income and education levels. Grappling with the economic challenges facing the Latino community might be the best way to increase their participation in and support for democracy.

California’s Latino voters shifted further right this year than in any election since 1994, when illegal immigration was also front of mind for many voters. This follows a rightward shift in the 2022 midterms. We may be seeing the early signs that Latinos are moving from not voting because of their stagnant economic prospects to casting their ballots for Republicans instead of Democrats. We are undeniably witnessing that trend nationally, and California may follow suit.

Latinos are the fastest-growing segment of the working class, and the issues that drove their older generations are not driving their younger voters today. But an economic agenda for them could generate as much zeal as advocating for the undocumented did in the previous generation.

The Proposition 187 era is over. The campaign for that initiative was an ugly stain on the state’s history, but it no longer defines our politics today. We can and must protect and care about the state’s undocumented people; that is a lesson we must never forget. But the ballots cast and the message sent by Latino voters themselves show they’ve had enough of policymakers whose preoccupation with the undocumented comes at the expense of working- and middle-class citizens.

Mike Madrid is a political consultant and the author of “The Latino Century: How America’s Largest Minority Is Changing Democracy.”

Source link