-

Newsom touts his economic plans in California’s conservative regions - 7 mins ago

-

Trump Won’t Care that RFK Jr. Compared Him to Hitler, Ex-Aide Says - 29 mins ago

-

N.Y.C. Housing Plan Moves Forward With an Unexpected $5 Billion Boost - 47 mins ago

-

NFL Coach Who Got Fired Reveals Tricking Ian Rapoport Into Breaking False News - about 1 hour ago

-

Want to see the Menendez brothers’ hearing? Enter the lottery - about 1 hour ago

-

China’s Hacking Reached Deep Into U.S. Telecoms - 2 hours ago

-

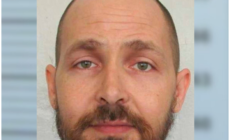

Carey Dale Grayson Final Words Before Alabama Execution - 2 hours ago

-

He led a darknet drug trafficking market dubbed ‘rickandmortyshop.’ Now he’s going to prison - 2 hours ago

-

The 4 Republican Senators Matt Gaetz Believed Would Tank His AG Nomination - 2 hours ago

-

Inside the Lobbying Career of Susie Wiles, Trump’s New Chief of Staff - 2 hours ago

Aging Bridge Is a Flashpoint in Competitive Washington State House Race

The first thing Representative Marie Gluesenkamp Perez told donors gathered at a recent wine-and-cheese campaign fund-raiser was of the role she played in securing $600 million in federal funding to rebuild one of the region’s main arteries, the aging Route I-5 bridge.

“Bringing that grant home was a dogfight,” said Ms. Perez, 35, a first-term Democrat from a rural, working-class district in Washington State that twice voted for former President Donald J. Trump, and who is facing one of the toughest re-election races in the country this year.

“My community is going to build that bridge,” she told the roomful of gray-haired donors gathered in a packed living room in Washougal, Wash., with giant windows overlooking the Columbia River. “This is our work.”

Ms. Perez considers this funding to be a major coup for her district and her re-election campaign. But the bridge in one of the country’s most competitive districts has become a political piñata in the race, which is all but certain to pit Ms. Perez against the far-right Republican Joe Kent, whom she beat in 2022 by less than 1 percentage point.

Mr. Kent, who denies the legitimacy of the 2020 election and has referred to those jailed for taking part in the Jan. 6, 2021, attack on the Capitol as “political prisoners,” has branded the reconstruction plan an “Antifa superhighway.” He has claimed that the proposed project, which includes a light rail and tolls, will bring unwanted urban elements from Portland into the car-centric, predominantly white community of Clark County, Washington, effectively serving as “an expressway for Portland’s crime & homeless into Vancouver,” as he wrote on social media.

It is an example of how Republicans, many of whom opposed President Biden’s sweeping $1 trillion infrastructure law, are seeking to transform even the most basic of local issues into battlegrounds in the nation’s culture wars in elections this year in which control of Congress is at stake. Mr. Kent’s attacks, which rely on buzzwords of the hard right, place the bridge at the center of a national political discussion that vilifies the left and plays on fears of demographic change.

“We don’t want the problems of downtown Portland dumped right into our district in Vancouver,” Mr. Kent said recently in a Facebook Live chat. “If you look at the murder rate, the crime rate, that’s the last thing we want in Vancouver.”

Republicans have long opposed making investments in mass transit, favoring spending on highways instead. Mr. Kent says he wants the historic bridge to be preserved, with more highway lanes built elsewhere to alleviate congestion.

Mr. Kent declined to be interviewed, agreeing to provide comment for this story only in writing. After The New York Times sent his campaign a list of questions, his aides blasted it out in a news release along with responses.

In the release, Mr. Kent denied that he was playing on racist fears in opposing the bridge project and accused Ms. Perez of lying about her role in funding it, even as he blamed her for mishandling it.

“The drug addicts and criminals in their tent colonies that are spreading their crime from Portland into Vancouver are almost entirely white, and Antifa is overwhelmingly white,” Mr. Kent wrote.

While Portland is predominantly white, it has the largest immigrant population in Oregon, and has seen more than 1,400 refugees arriving from Afghanistan since August 2021. As the city has struggled to provide temporary shelter to migrants arriving from the southern border, Mr. Kent has claimed that Democrats are allowing “illegal invaders” to flood into American communities.

Mr. Kent said Ms. Perez’s true priorities were “protecting biological men’s rights to invade women’s sports, spaces and bathrooms” and said her entire involvement in funding the new bridge consisted of “writing a letter to Pete Buttigieg,” the transportation secretary.

In an interview, Mr. Buttigieg said Ms. Perez “absolutely had a role” in the project being chosen to receive the largest grant of its kind.

“We choose projects based on their merits,” Mr. Buttigieg said. “Effective advocates help to illustrate those merits.”

Built in 1917, the Interstate 5 bridge is one of two major crossings between Washington State and Oregon, with about $132 million worth of freight crossing the bridge every day, as well as about 69,000 commuters from Ms. Perez’s district. It is the main connector for an entire region of the Pacific Northwest, but it is widely believed to be at the end of its life.

The span has become so congested that for many hours a day, vehicles crawl across at 35 miles per hour. The entire structure is supported by pilings of Douglas fir sunk in mud — “pretzel sticks in chocolate pudding,” as the mayor of Vancouver, Anne McEnerny-Ogle, likes to describe it — that puts it at high risk of total collapse in the event of a major earthquake.

“There are projects that are just too large and too complex to be done through existing funding mechanisms,” Mr. Buttigieg said, explaining why the project had received such a large grant. “There needs to be extra support.”

He described the Interstate 5 bridge as the “worst trucking bottleneck in the region” and said it was an example of “a bridge designed to the state of the art 100 years ago that can and must be replaced.”

In 2022, Ms. Perez, who ran an auto repair shop, beat Mr. Kent, a Trump-endorsed retired Green Beret whose wife had been killed fighting ISIS, by just two votes in each precinct in the district. Now Mr. Kent is back, hoping to be swept to victory with Mr. Trump at the top of the ticket.

There are other Republicans running in the primary, but Mr. Kent’s emergence from that small field is already considered a fait accompli; the state Republican Party suspended its bylaws so it could endorse him in the primary and outside groups working to keep Republican control of the House are planning to back him.

And Mr. Kent has already turned the Interstate 5 bridge into a flashpoint of his campaign.

“Voters all across the district are rallying behind my message of common sense conservatism: Build a bridge with no tolls and no light rail, get spending and inflation under control,” he said.

As she crisscrossed her district in the rain and snow in her Toyota Tundra last week with her dog Uma Furman in tow, Ms. Perez said she tries not to think too much about Mr. Kent. “I really try not to get in his head that much. I have to not get in D.C.’s head and not get in Joe’s head.”

Ms. Perez tries to stay in the mind-set of her constituents. On Capitol Hill, Ms. Perez is the rare Democrat who often breaks with her party on major votes, often drawing the ire of progressives who she says do not value the priorities of the working class.

“On the floor, I really have to pay attention to my votes,” she said. “It’s this constant analysis of, ‘How much can I afford to piss off people to do what I think is right?’”

Ms. Perez was one of four Democrats who voted for an annual defense policy bill that Republicans loaded full of conservative social policy mandates that would limit abortion access, transgender care and diversity training for military personnel. She defended the vote, saying it was important to support the military and that the Senate was always going to “clean up” the bill by stripping out the partisan amendments she didn’t agree with.

She also sided with Republicans on a bill to repeal Mr. Biden’s student loan relief initiative. And Ms. Perez has supported the censures of two Democrats, Representatives Jamaal Bowman of New York and Rashida Tlaib of Michigan. Still, Mr. Kent has portrayed her as in lock-step with Democrats and Mr. Biden, attacking her for opposing a hard-line immigration bill, among others.

It has left Ms. Perez in a bit of a political no-man’s land. In the capital, her social circle consists mostly of two Republican Bible study groups, one of which includes Representative Richard Hudson of North Carolina, the current chairman of the Republican House campaign arm that is actively targeting her for defeat.

Ms. Perez, along with other Democrats representing districts that Mr. Trump won, “got a pass last cycle; no one laid a glove on them,” Mr. Hudson said at a recent briefing with reporters. He said his job was “educating voters about their records.”

Despite that, Ms. Perez, whose father was an Evangelical pastor, says she often feels more at home among religious Republicans.

“I feel like my party is embarrassed I’m a Christian,” she said. She is broadly dismissive of some of the values of her own colleagues, whom she views as out of touch.

“I hear my colleagues complain about not making enough money,” she said of her fellow lawmakers, who earn $174,000 a year. “You know what the average income in my community is? You should be ashamed of yourselves.” (The average income in her district is $43,266.)

When Ms. Perez was elected, her Republican opponents tried to tag her as someone who would operate as an undercover, West Coast version of Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, another young, working-class woman whose election to Congress no one had seen coming. But Ms. Perez said she has little in common with the progressive star from New York, nor has she had much to do with any of the other young women in Congress, even socially.

“Our districts are really, really different,” she said of Ms. Ocasio-Cortez. “It is very lonely, working all the time. You go back to your apartment and eat some frozen peas and go to bed.”

At the evening fund-raiser last week, Ms. Perez focused mostly on her work on local issues, but pressed by donors eager to vent their concerns about Mr. Biden and his re-election campaign, she had little praise to offer.

“I’m not here to apologize for his performance or his messaging,” Ms. Perez said. “I have a lot of dissatisfaction with how Biden’s using his power, but when it becomes a choice between that and Trump?”

Later, sitting in her old office in her auto shop before catching a flight back to Washington, Ms. Perez tried not to get too worked up about what would happen if she lost her re-election race. She would return to this more simple life, she said, and be happy not to miss so many bedtimes with her toddler. But the idea of losing to Mr. Kent was hard to swallow.

“It’s just really obnoxious and patronizing when he’s assuming the mantle of fighting for the little guy,” she said. “It might work for one election cycle, but people are going to need jobs. It works until the bridge collapses — and then what?”