-

Nearly every house on their west Altadena block was incinerated. Nearly everyone will be back - 20 mins ago

-

Greenpeace’s Fight With Pipeline Giant Exposes a Legal Loophole - 34 mins ago

-

Map Reveals Only 5 Metros Where Minimum Wage Workers Can Afford Rent - 38 mins ago

-

Edison neglected maintenance of its aging transmission lines before the Jan. 7 fires. Now it’s trying to catch up - about 1 hour ago

-

Personal Trainer Criticized for Promoting ‘Skinny Legs’ Workout Advice - about 1 hour ago

-

Warner Bros. Urges Shareholders to Reject Paramount Takeover Bid, Saying Ellisons ‘Misled’ Them - about 1 hour ago

-

‘Both sides botched it.’ Bass, in unguarded moment, rips responses to Palisades, Eaton fires - 2 hours ago

-

Andy Cohen’s 9-Word Response to Being Told He’s Not a Real New Yorker - 2 hours ago

-

Trump Orders Blockade of Some Oil Tankers to and From Venezuela - 2 hours ago

-

After a rocky start, rebuilding in the Palisades and Altadena is gaining momentum - 2 hours ago

After a rocky start, rebuilding in the Palisades and Altadena is gaining momentum

In the race to show progress in rebuilding Palisades and Altadena after this year’s catastrophic fires, Los Angeles city and county both stumbled out of the blocks.

In November, the first home reported rebuilt turned out to be an Altadena ADU conversion of the burned garage of a house that survived the Eaton fire. A few days later, Los Angeles touted its first completion only to face criticism because the house was a builder spec home permitted for demolition and rebuilding before the Palisades fire destroyed it.

Despite initiating procedures to speed the rebuilding process, both city and county have faced backlash from fire victims who complain of being slowed by stifling bureaucracy.

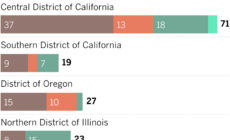

Now, a preliminary Times analysis of permit data published by the city and county shows that progress in both communities is beginning to gain momentum and falls in the middle compared to the rebounds achieved by two other cities that faced the destruction of whole communities after recent wildfires.

According to The Times’ analysis, the Los Angeles County Department of Public Works as of Dec. 14had issued rebuilding permits for about 16% of the homes destroyed in Altadena. The Los Angeles City Department of Building and Safety was just under 14%.

Those percentages fall between the performance of cities recovering from two recent California fires, but the spread was wide. Eleven months after the Tubbs fire, Santa Rosa had issued permits for 29% of its destroyed homes while fewer than 3% of homes destroyed in Paradise during the Camp fire had obtained permits at that stage.

The city and county lagged behind both those cities by about two months in their first completed homes. Santa Rosa and Paradise each had a home ready for occupancy in under eight months compared to slightly over 10 months in Palisades and Altadena.

According to the analysis, L.A. City is processing applications faster, with an average of 79 days from an application to issuance of a permit, compared to 131 days for the county.

But fire victims in Altadena are filing applications at more than twice the rate as those in Palisades. The county had applications pending for just over 3,000 residences, making up 52% those destroyed. Just over 1,400 applications on file with the city account for about 32% of homes destroyed.

In total, the county had issued permits for 931 residences by Dec. 14and the city 604.

A Times analysis published this year found that recovery varied markedly by fire and jurisdiction after the five recent wildfires that each destroyed at least 1,000 homes.

In total, nearly 22,500 homes were lost in the five blazes, which occurred from 2017 to 2020. Just 8,400 — 38% — had been rebuilt as of April per The Times’ analysis.

The 2017 Tubbs fire was at the high end with 79% of homes rebuilt. The 2018 Carr and Woolsey fires were in the middle, with 47% and 41% rebuilt, respectively, and the 2018 Camp fire was at 26%.

Excluding the 2020 North Complex fire, which was only 5% rebuilt, they all followed a pattern. It took seven to nine months for the first house to be completed. Development rose from there and reached its monthly peak between the second and third year. By year four, progress dropped significantly.

“It’s a marathon sprint,” Andrew Rumbach, a senior fellow at the Washington-based Urban Institute, where he studies disaster response, told The Times in September. “It’s going to take a really long time and it’s going to be really intense for a very long time.”

::

Construction crews work on building a home in the Palisades fire zone Oct. 8.

(Allen J. Schaben/Los Angeles Times)

All sorts of personal circumstances factor in why people take more time than others to apply for a permit: residents were under-insured and don’t have the cash to rebuild; they’re still deciding if they want to go through the hassle of rebuilding or just sell; they’re enlarging and remodeling their homes, which extends both the design and permitting phases.

Dennis Smith lived in the Palisades for 25 years before the January fire took his home. He spent the first few months after the fire navigating his insurance and figuring out how much money he’d have to rebuild. Best-case scenario, he found out his insurance would cover around two-thirds of the cost.

Covering the rest himself meant he wouldn’t have enough cash on hand to pay for a contractor, so he’s taking on the role himself. After figuring out insurance, he spent the next few months interviewing architects and researching building materials, since he’s decided to build with 100% non-combustible materials. It’s a wise long-term decision, but it’s no time-saver. The vast majority of architects Smith spoke to were used to framing with wood, so introducing alternative materials meant spending valuable weeks tweaking plans and tinkering with the budget.

Smith is currently in the structural engineering phase. He needs to get his architectural plans — which call for a like-for-like rebuild and an ADU that combine for 3,000 square feet — approved before he can take it to the city for permits.

He’s heard from neighbors that the permitting process has been relatively quick, around five to six weeks for some. After that, he’s hoping he can finish in a year, but bracing for it to take 18 months.

“All these people are building at the same time, so there’s a limited labor pool,” Smith said. “I was hoping to get a big group together so we could save time and money by building with economies of scale, but that was a pipe dream. Everyone’s timeline is different, and everyone’s budget is different.”

Debra and Elton Blake make their way around their property that was destroyed by the Eaton fire as their new home is in the beginning stage of the rebuild on Oct. 16 in Altadena.

(Jason Armond/Los Angeles Times)

Ignacio Rodriguez, founder and chief executive of IR Architects, is currently building 16 custom homes for families in the Palisades. The projects are all in different phases — some in construction, some in planning, some still in design — but he’s been pleasantly surprised with how quickly the city has been turning permits around.

“Permitting typically takes around four to six months, but it’s been taking two to three months,” he said. “The Department of Building and Safety has been great. Inspections are smooth, and inspectors are available with no delays.”

Rodriguez has been building homes in the Santa Monica Mountains for the past 12 years and said things are moving slightly quicker in the wake of the Palisades fire than they did after past fires.

He said the main hold up has been with other city agencies — Water and Power, Public Works and Sanitation.

He claimed understaffing has been an issue, and said it can take weeks for comments to come back on applications. The fire also damaged power lines and sewer lines, so there’s ambiguity on what sections are being repaired, upgraded or kept the same, which leads to construction delays.

Typically, Rodriguez said the planning phase takes four months, and the permitting phase takes another two or three. From there, he’s telling homeowners that construction takes 12 to 15 months for custom homes without a basement, or 18 to 24 months for custom homes with a basement.

1. John Dyson, right, wife Darlena Dyson and LA County Supervisor Kathryn Barger tour the ADU that Deborah Dyson, left, John’s older sister, will live in. (Myung J. Chun/Los Angeles Times) 2. John Dyson and his wife Darlena received the first certificate of occupancy for a rebuilt residence in the Eaton fire burn area in West Altadena this month. (Myung J. Chun/Los Angeles Times)

In Altadena, Leticia Montanez, 62, knew that if she didn’t act fast towards rebuilding, a bottleneck of residents seeking architects, contractors, permits and building materials would slow down her ability to get back to her land. The JPL engineer lived in her home on Santa Anita Avenue for more than 20 years before the Eaton fire destroyed it in January.

By February, she had already found an architect to reconstruct a blueprint of her four-bedroom, three-bath ranch-style home using photos and aerial images. After several months waiting on a review from Los Angeles County Building and Safety, she said she goosed the process along by sitting in the county office on Woodbury Avenue during her lunch breaks. Her rebuilding permit was approved in September.

“I was able to get through the process fast because there weren’t a lot of people moving through it,” Montanez said. She said that the water department’s confirmation of service took her only three days versus a current wait time of several months.

The foundation has been laid and lumber has been secured. She hopes that by next September, she and her two cattle dogs will be back home. She knows she’s returning to a different Altadena, but going home is her ultimate goal. “I’m going to get back to just living,” she said.

A note about data

Due to the different jurisdictions’ data keeping, it was not possible to make pinpoint accurate comparisons of the number of homes destroyed by the fire that have permits to rebuild. The Times had to compensate for ambiguities and apparent data entry errors, often by taking into account freehand notes on a permit that painted a clearer picture of the project.

The Times found, for example, records of projects categorized in primary fields as new buildings but described in the freehand notes as a garage or cabana. About a third of the earliest records from the county had no data categorizing the type of structure, and The Times extracted that information, as best as possible, from the freehand notes. The result is that the numbers can differ from those on city and county rebuilding dashboards. Also, ancillary permits such as for plumbing and electricity, which are counted on the L.A. City dashboard, were excluded.

Source link