-

Jimmy Kimmel Teases ‘Melania’ - 27 mins ago

-

Santa Clarita girls hockey team members injured in fatal multi-vehicle crash in Colorado - 28 mins ago

-

The End of Nuclear Arms Control - about 1 hour ago

-

Sad News Surfaces on Famed Notre Dame Coach Lou Holtz - about 1 hour ago

-

Panama Court Strikes Down Hong Kong Firm’s Canal Contract - 2 hours ago

-

Dr. Oz accused L.A. Armenians of fraud. Newsom files civil rights complaint - 3 hours ago

-

Trump Expected to Announce Kevin Warsh as Fed Chair - 3 hours ago

-

NBA Announces Historic Cooper Flagg News After 49-Point Performance - 3 hours ago

-

Trump and First Lady Attend Premiere of ‘Melania’ at Kennedy Center - 3 hours ago

-

Trump Sues I.R.S. Over Tax Data Leak, Demanding $10 Billion - 4 hours ago

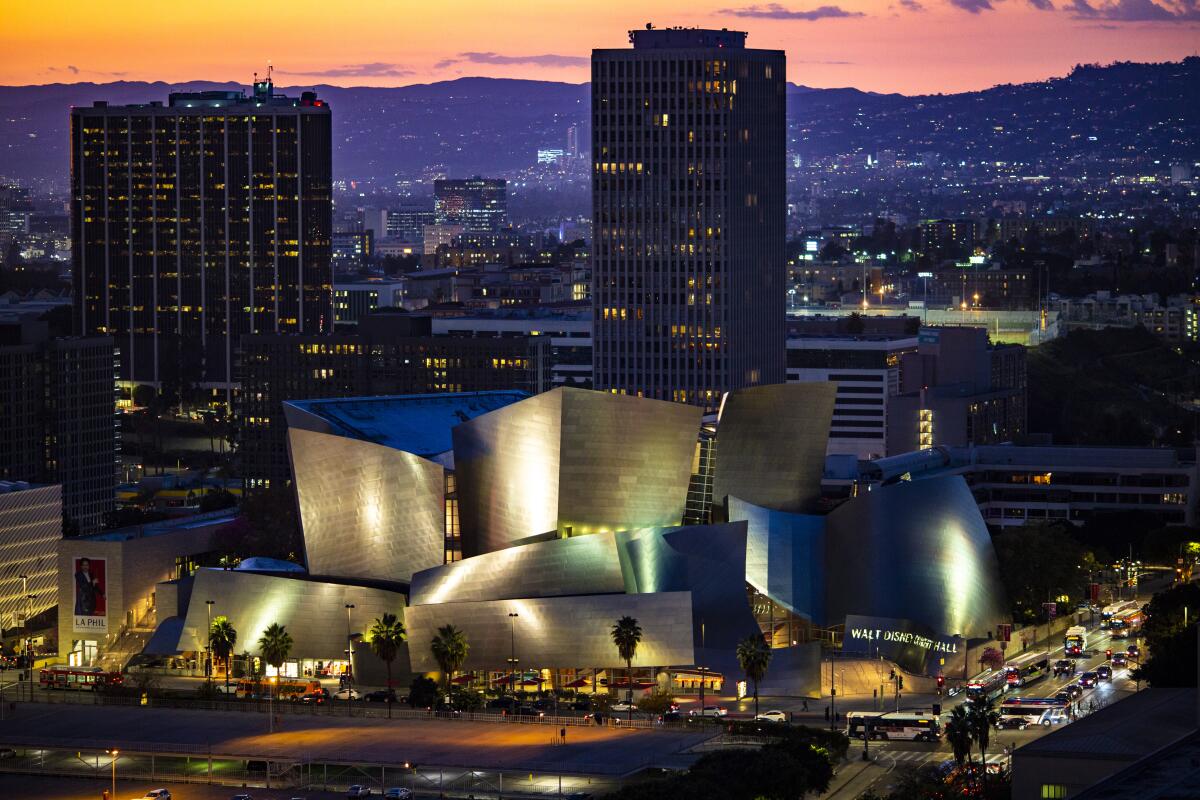

Frank Gehry dead: Disney Hall architect transformed L.A.’s landscape

Architect Frank O. Gehry, who brought an alluringly new kind of shape-making to his profession even as he fundamentally changed the reputation and civic landscape of his adopted hometown of Los Angeles in such projects as the shimmering Walt Disney Concert Hall on Grand Avenue, has died. He was 96.

Gehry, who arrived in L.A. as an aimless teenager just after World War II and went on to become the most famous and one of the most influential architects in the world over a prolific six-decade career, died Friday at his home in Santa Monica following a brief respiratory illness, Gehry Partners chief of staff Meaghan Lloyd confirmed to The Times.

Gehry had been widely respected among L.A. architects since the 1970s, but his global fame grew from high-level productivity late in his career. This phase, in which his firm, Gehry Partners, pioneered new ways of using technology to help realize geometrically complex buildings, began with the completion of an ambitious satellite branch of the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain. It opened to the public in 1997, the year Gehry turned 68.

The museum was widely praised for its breathtaking and sinuous profile and dramatic relationship to the Nervión River at its feet. Just as important, it helped reenergize and bring new media attention to architecture. Still looking for direction after the breakdown of the Modern movement and the repeated false starts of a historically minded Postmodernism, the profession badly needed a boost.

The Guggenheim Bilbao in October 1997, when it opened to the public.

(Santiago Lyon / Associated Press)

The new Guggenheim suggested a fresh, dynamic direction: architecture whose appeal resided in the ravishing large-scale curves made possible with digital design software and almost perfectly suited to architectural photography and display in the pages of newspapers and magazines. Suddenly cities and museums were clamoring to hire Gehry — or some other member of the growing class of top-tier star architects, or “starchitects” — to try to replicate the windfall of attention and tourism dollars the new Guggenheim had produced. That windfall even earned its own nickname: the Bilbao Effect.

On the heels of the Guggenheim came a series of other triumphs for Gehry. They included the opening in 2003 of the long-delayed Disney Hall, designed before the Bilbao museum but completed after it, and the Richard B. Fisher Center for the Performing Arts at Bard College in New York.

Some critics complained that Gehry’s firm, which had turned into a global powerhouse, was spreading his talents too thin, leading to disappointments such as the Experience Music Project in Seattle, finished in 2000. There were also whispers that Gehry, in an effort to recapture the Bilbao magic, was chasing ill-conceived museum commissions around the world.

In projects like the Guggenheim branch in Abu Dhabi, commissioned in 2006, it was suggested that the huge budgets had raced past a clear idea of what the building would mean culturally or even what kind of artwork it would hold. It came as little surprise when the building was plagued by delays. Originally scheduled to open in 2012, the Guggenheim pushed back the opening date on multiple occasions, with 2026 currently serving as the target opening — 20 years after the project was announced.

Frank Gehry in his Playa Vista office in 2015.

(Richard DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

But Gehry always seemed to have a project waiting in the wings to silence his detractors. Disney Hall was his answer to the charge, repeated frequently over the years, that he was more skilled at producing architectural sculpture than answering to practical or functional requirements. The concert hall is a brilliant, eye-catching piece that helped fill a literal and symbolic civic hole at the top of Bunker Hill. It also holds an auditorium that functions superbly in acoustic terms and gave the Los Angeles Philharmonic a new visibility. The hall is at once a luminous public landmark and a workhorse.

Similarly powerful was another late-in-life triumph, the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris, a museum built to hold the collection of the French business magnate and art collector Bernard Arnault. When it opened in the fall of 2014 in a quiet corner of the Bois de Boulogne, the large park on the west side of Paris, it suggested a newly refined, even urbane direction in Gehry’s late work.

The dramatic forms are still there, this time in glass, wrapping the body of the building like huge transparent sails, but they are part of an architectural composition as notable for its balance and elegance as for its boisterous energy. This time it was the notion that Gehry’s work was visually chaotic, not merely unresolved but undisciplined, that was exposed as a severely limited reading of his work.

What the best of Gehry’s late projects have in common is not only virtuosity in their form-making, but also a remarkable kind of humanism. This was the best-kept secret of Gehry’s career: how dedicated he was to, and how skilled at, the basic task of architecture, which is to create spaces that respect and accommodate human scale.

In the architect’s finest work, proportion as well as attention to light and shadow are expertly handled, taking advantage of skills honed over many decades. His most memorable rooms are as carefully and intelligently put together — and in their charismatic and forward-looking energy, as quintessentially American — as the most fluid descriptive prose by F. Scott Fitzgerald, the most freewheeling artwork by Robert Rauschenberg or the most stirring fanfare by Aaron Copland.

Walt Disney Concert Hall is masterful in both function and form.

(Kent Nishimura / Los Angeles Times)

Gehry was born Frank Owen Goldberg on Feb. 28, 1929, in Toronto. (He would change his last name to Gehry in 1954.) Gehry’s father, Irving, was a salesman and truck driver who had trained as a boxer and moved to Canada from New York, his hometown, as a young man. His mother, Thelma, was born in Poland and immigrated to Toronto with her family as a child.

He was not close to his father, but his mother exposed him to music and art. Her parents, Leah and Samuel Caplan, spent extended time with Gehry in Toronto as a child.

“Gehry says his urge to reinvent order was born in the back room of his grandfather’s hardware store in downtown Toronto,” Leon Whiteson wrote in The Times in 1989. “There he tinkered with dismembered clocks and toasters, and the pathos of dismantled gears, springs and wires infected him with a tenderness for mechanisms that spill their guts for all the world to see.”

After finishing high school in 1947 at age 17, Gehry decided to move with his parents to L.A. Gehry’s father, who had suffered a heart attack that year, had been advised by a doctor to move to a gentler climate and ease up on physical labor.

“Los Angeles when I got here was brash, raucous, frontier,” Gehry told journalist Barbara Isenberg, whose book “Conversations With Frank Gehry” was published in 2009. “Carney business. The movies. The development was vast and rampant. Whole neighborhoods seemed to spring up instantly in desert locations.”

For Gehry, this seemingly chaotic cityscape “represented a kind of openness, and freedom because it was risk-taking somehow. There was an edge to it. Some of it was greedy and awful, and some of it was positive and moving.”

Frank Gehry takes a construction tour of his Judith and Thomas L. Beckmen YOLA Center in Inglewood in 2020.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

Gehry enrolled in night school at L.A. City College, where he took art and architecture classes, then went to USC, where he studied ceramics with artist Glen Lukens, as well as architecture.

In 1951 Gehry became a naturalized U.S. citizen. The following year he and Anita Snyder, whom he met when he delivered furniture to her parents’ house while working as a driver for the Vineland Co., were married. He was 22 and she 18. They divorced in 1966.

It was Anita, Gehry said, who convinced him in 1954 to change his last name from Goldberg to the less Jewish-sounding name of Gehry, which is of Swiss German origin. Gehry said his wife and her mother helped him select from a group of names beginning in G. Gehry liked his initials, F.O.G., and didn’t want to give up the acronym.

“I learned I was passed over for an architectural fraternity because I was a Jew,” Gehry told Isenberg. “I didn’t care, but it was evidence of anti-Semitism to me. Then a guy I knew came to me and said, ‘Change your name and we can start a partnership.’ That kind of stuff is what pushed my ex-wife to lobby for a name change, and why I finally gave in to it.”

Gehry earned a bachelor’s degree in architecture from USC in 1954. After a stint in the Army in Atlanta from 1954 to 1956, he returned to L.A. to take a job in the office of Victor Gruen, a Viennese-born architect known for helping invent the American shopping mall. He left to study urban planning at Harvard Graduate School of Design, came back to L.A. to work again for Gruen and the prolific firm of Pereira & Luckman, helmed by William Pereira and Charles Luckman, and then spent a year working in Paris.

He returned to L.A. for good in 1962 and, at 33, opened his own firm with a partner, Greg Walsh. At first his projects were fairly well-behaved and faithful, at least outwardly, to the Modernist principles he had learned at USC: flat roofs, restrained geometry. But he began to absorb important cues from the postwar commercial landscape of L.A.

The first design to gain wide attention, a 1965 loft and studio for graphic designer Lou Danziger on a busy stretch of Melrose Avenue, was typical of this combination: A spare, even self-effacing stucco box, plain outside and filled with light and surprising spatial complexity inside, it looked Modern but also suggested sympathy for the postwar visual chaos of L.A. evident in the work of artists such as Ed Ruscha and David Hockney.

Indeed, relationships with visual artists, more than with architects, sustained Gehry during the early years on his own and began to lead the way to bigger commissions. A house in Malibu for painter Ron Davis, completed in 1972 and featuring a trapezoidal frame, was among his first efforts to break from the Modernist box and move toward a more expressionistic architectural language.

As the office grew, Gehry took on more houses and larger commissions, including a series of store interiors for the Joseph Magnin chain. But it was the way he remodeled the Santa Monica house he shared with his second wife, Berta Aguilera, a native of Panama he married in 1975, that first brought him national and international attention.

An architectural model of Frank Gehry’s residence on view in the architect’s retrospective at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 2015.

(Carolina A. Miranda / Los Angeles Times)

It was a small, pink, two-story bungalow built in 1920 that he and Berta bought it in 1977. Gehry quickly set to work remaking it — taking off huge sections of its facade and replacing them with glass, corrugated metal and exposed wood framing. (A later reworking added chain-link fencing.) His inspiration was not any architectural theory or school so much as the workaday landscape of Southern California itself, the brash free-for-all he had noticed as soon as he arrived in L.A.

The house attracted critics and fellow architects throughout the 1980s. The attention it brought him led to a string of significant commissions in that decade. Gehry designed several buildings for the Loyola Law School campus near downtown L.A. He turned a warehouse in Little Tokyo into the Temporary Contemporary, later renamed the Geffen Contemporary, for the Museum of Contemporary Art (a building that was better received than the design of MOCA’s more formal main museum building by Japanese architect Arata Isozaki.)

Throughout his career, Gehry would continue to show a knack for sensitively repurposing old buildings. His Pierre Boulez Saal in Berlin, which opened in 2017, transformed a historic warehouse once used to store opera sets into a beckoning communal performance space. And in 2021, he transformed a drab 1960s bank branch in Inglewood into a graceful rehearsal and performance space for Youth Orchestra Los Angeles.

“It’s not a precious building,” he said of the YOLA project upon its completion. “But it’s precious in what it does.”

Frank Gehry’s team reimagined a Security Pacific bank branch in Inglewood as a performance and rehearsal space for Youth Orchestra Los Angeles.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

But it was his firm’s design for Disney Hall that served as the professional tipping point. In 1988, Gehry won a high-profile competition to design a new home for the Los Angeles Philharmonic on Grand Avenue in downtown L.A., an expansion of the Music Center campus next door. As the only L.A. architect in the field, he beat out a group of finalists that included several of the biggest names in 1980s architecture, including Hans Hollein of Austria and London-based James Stirling.

The victory was at least partial vindication after years in which Gehry struggled to earn many significant commissions, particularly for civic and cultural projects, in L.A.

Though construction of the concert hall would be delayed, the achievement helped him win the Pritzker Prize, architecture’s top honor, in 1989. Gehry was the first L.A. architect to win a Pritzker. The jury citation read, in part, “Refreshingly original and totally American, proceeding as it does from his populist Southern California perspective, Gehry’s work is a highly refined, sophisticated and adventurous aesthetic that emphasizes the art of architecture.”

Before Disney could be realized, the transformative Bilbao design helped make Gehry a household name. In the early 1990s, New York’s Guggenheim Museum, beginning what would become a global expansion, commissioned Gehry to design a branch in Bilbao. The building, clad in titanium panels and almost impossibly beautiful in photographs, opened in 1997. A review that appeared on the cover of the New York Times Magazine, written by the architecture critic Herbert Muschamp, carried the headline “The Miracle in Bilbao.”

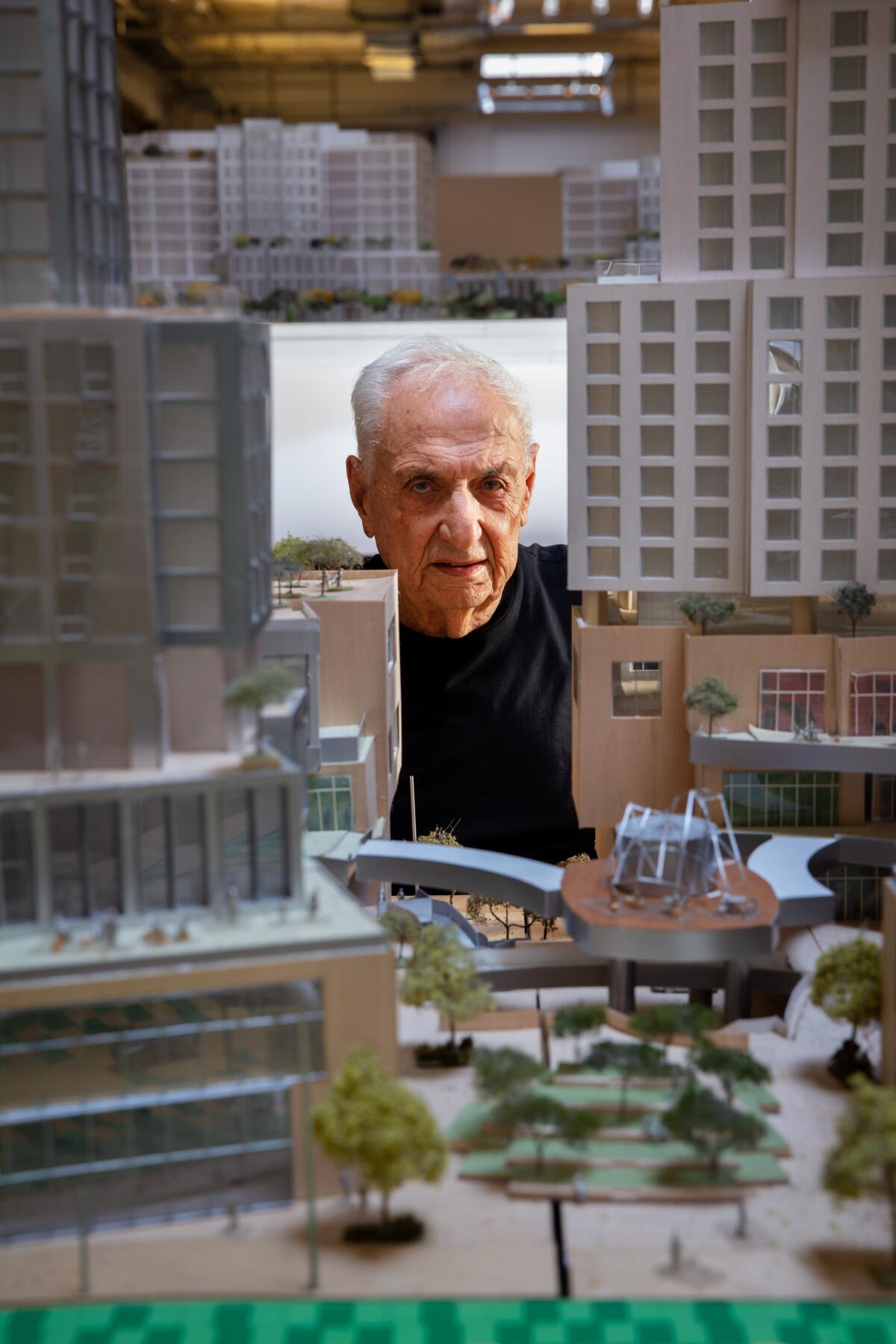

Frank Gehry peers through a model of his Grand Avenue Project in his architectural studio in May 2019.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times)

The opening of the building was almost perfectly timed for maximum impact within the profession. Architecture was in a funk, aimless and beaten down by the recession of the early and middle 1990s. “This building’s design and construction,” Muschamp wrote, “have coincided with the waning of a period when American architecture spectacularly lost its way.” He called the museum not just “wondrous” but “a Lourdes for a crippled culture.”

That rave notice and the many others that followed, along with the rapturous reports sent back by artists and tourists alike, helped shame L.A. into reviving the floundering plans for Disney Hall.

By 1998 construction on the hall had resumed. And five years later, in 2003, the Gehry building that was supposed to precede the museum in Spain, clad in shimmering steel panels in place of Bilbao’s titanium, had opened at the top of Bunker Hill.

Confetti rains down on the Los Angeles Philharmonic at the conclusion of a gala concert at Disney Hall in 2019.

(Francine Orr / Los Angeles Times)

It was a startling symbol of architectural talent. It was also a reminder of how long it took L.A. to fully recognize the brilliance of an architect who since his teenage years had called the city home — and indeed had put a little bit of Southern California, its looseness and tolerance, into almost every building he designed.

Gehry is survived by his wife, Berta, and four children.

Hawthorne is The Times’ former architecture critic. Former Times columnist Carolina A. Miranda contributed to this report.

Source link