-

Mark Zuckerberg’s Meta Donates $1 Million to Trump’s Inaugural Fund - 25 mins ago

-

Today’s ‘Wordle’ #1,272 Answers, Hints and Clues for Thursday, December 12 - 30 mins ago

-

Nike and NFL Aim to Boost Global Reach with Decade-Long Collaboration - about 1 hour ago

-

In Aleppo, Jubilant Syrians Return to a Ravaged City and Toppled Monuments - about 1 hour ago

-

Donald Trump Announces New Role for Kari Lake - 2 hours ago

-

Dean of Students at Massachusetts School Charged With Conspiring to Traffic Cocaine - 2 hours ago

-

Outgoing House Republican: ‘The Less’ Congress Does, ‘The Better’ - 2 hours ago

-

Syria’s New Leaders Balance Huge Struggles Amid Disorder - 3 hours ago

-

Back-to-Back Bomb Cyclones Could Hit US - 3 hours ago

-

South Korea President Yoon Defends Martial Law Decree in Defiant Speech - 3 hours ago

He was Leslie Van Houten’s ‘hippie lawyer.’ Then, he defied Manson

When Charles Manson announced that he wanted Ronald Hughes to represent him at his murder trial, even Hughes seemed surprised. He was no one’s idea of a skilled defense attorney. He had passed the bar, after three failed attempts, just 10 months earlier. He had been Manson’s most frequent jailhouse visitor, serving as his “legal runner” — a glorified gofer — but had never tried a case.

Now, improbably, Hughes would take a key seat at America’s most-watched trial, with a client accused of masterminding the gruesome home invasion murders of actress Sharon Tate, grocer Leno LaBianca and five others.

In this series, Christopher Goffard revisits old crimes in Los Angeles and beyond, from the famous to the forgotten, the consequential to the obscure, diving into archives and the memories of those who were there.

Known as the “hippie lawyer,” with a bushy, unkempt beard, Hughes was a huge, amiable mess. He sometimes wore a love-bead necklace to court. He slept on a mattress in a two-car garage with holes in the roof. On the wall hung his UCLA law degree, decorated in psychedelic colors.

It was March 1970. Hughes had just turned 35. For those who studied Manson, there was a certain logic in the choice. Hughes spoke the language of the counterculture and had socialized with Manson before the cult leader’s 1969 arrest. Hughes was supposed to be another of Manson’s many puppets, a neophyte attorney who would be easily manipulated — or intimidated — to do whatever Manson demanded.

Soon, Manson appointed him as the attorney for 19-year-old Leslie Van Houten, one of three young female co-defendants. The former high school homecoming princess was accused of participating in the stabbing deaths of LaBianca and his wife at their Los Feliz home.

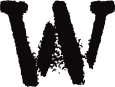

Charles Manson’s devoted co-defendants Susan Denise Atkins, Patricia Krenwinkel and Leslie Van Houten head to court in August 1970.

(George Brich/Associated Press)

“What is your relationship with Mr. Manson now?” a reporter asked Hughes.

“I think it’s a very friendly one, and always has been,” Hughes replied. “We’ve seen eye to eye on a great number of things.”

Hughes made a strong impression on people as sweet and friendly, an Army veteran from a conservative family who had served in Korea and then drifted into late-’60s Los Angeles counterculture.

It is unclear how or when he met Manson. Music might have been the connection. In 1968, Hughes was the road manager for an experimental psychedelic band called the United States of America, and Manson was an aspiring singer-songwriter.

At some point, Hughes began visiting the old movie ranch above Chatsworth where Manson lived with a ragged band of followers, mostly young women. They were known as thee Family, an outlaw commune of easy sex and free-flowing drugs, held together by Manson’s demented messianic charisma.

“He used to go out to Spahn Ranch and drop acid with them,” Stephen Kay, a Manson prosecutor, told The Times in a recent interview.

Hughes got the job as Van Houten’s attorney because Manson didn’t like the approach her prior lawyer, the skilled and experienced Ira Reiner, was taking.

“I tried to separate Leslie from the other defendants,” Reiner, who went on to serve as L.A. County’s top prosecutor and is now 88, told The Times. “She was very young, a cultist under the thrall of a cult leader. That was going to be my defense.”

Reiner asked potential jurors whether they could judge Van Houten on the evidence against her, and possibly acquit her, regardless of her desire to share whatever fate her co-defendants received. He asked whether they’d heard of the “hypnotic power” Manson wielded over followers.

“That didn’t go over well with Charlie,” Reiner recalled.

When Reiner visited his client in jail, he noticed a change in her. She had been friendly to him, even charming, but now she was coldness itself.

Charles Manson in December 1970 after a courtroom outburst resulted in his ejection, along with his three co-defendants, from the Tate-LaBianca murder trial.

(George Brich/Associated Press)

“Leslie’s whole demeanor changed. She said, ‘I think you should withdraw from the case.’”

Three of Manson’s young female disciples had shown up for the meeting. They sat in a semicircle behind Reiner, exuding menace.

“It was clear they meant it to be threatening. ‘You can do it this way or the hard way.’”

Reiner feared the Manson disciples would follow him, so he asked a sheriff’s captain to detain them while he left the jail.

“It’s not paranoia. Paranoia is only an unreasonable suspicion. They killed enough people that when they threatened you, you took it seriously,” Reiner said. “The next day, I went into court and said, ‘My client would like a substitution.’”

And so in July 1970, five weeks into the trial, Hughes signed on, without pay, to represent Van Houten.

Reiner tried to warn Hughes about the Manson clan.

“You’re dealing with homicidal maniacs. Don’t get too close.”

Hughes was slovenly and ill-prepared. Kay recalled that at one point, Hughes had just two ties — one featuring Mickey Mouse, the other a nude lady. When the judge reprimanded him for not wearing a jacket, Hughes borrowed one from a Newsweek reporter that was much too tight for his 250-pound frame. He began buying discount suits from auctions at the MGM movie lot and liked to show off the names of actors, such as Raymond Burr, who had worn them.

Once, the judge held Hughes in contempt of court for saying “s—” and gave him a choice: pay a $75 fine or spend the night in jail.

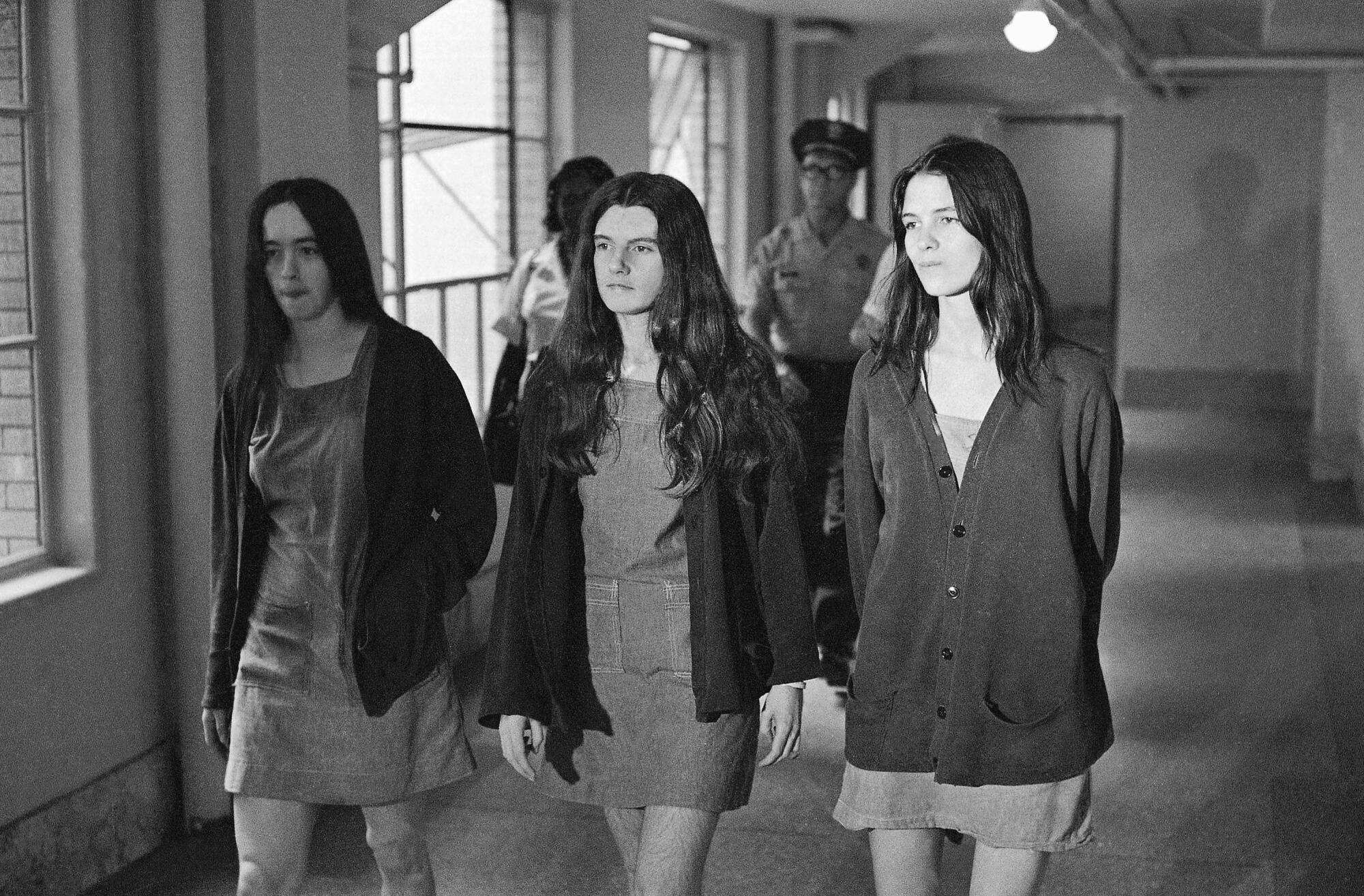

Ronald Hughes was handpicked by Charles Manson to defend him against charges that he masterminded a series of murders in Los Angeles in August 1969.

(George Brich/Associated Press)

“I’m a pauper,” Hughes said, and checked into jail. Afterward, he told reporters, “It was a good experience. I would have paid another $75 to go through it.”

The trial was briefly delayed when he was jailed on a traffic warrant, and again when a highway patrolman ordered him to get his decrepit car off the road.

“He was one of a kind,” said Kay. “I never before or after ever saw an attorney in court that looked anything like him. He was so overmatched in the courtroom. … Here he was on this so-called crime of the century, and he was just trying to tread water.”

Hughes stumbled but learned. He skillfully questioned a fingerprint expert and established that Van Houten’s prints were not found at the LaBianca home.

The Los Feliz home where Leno and Rosemary LaBianca were found murdered, photographed on Aug. 11, 1969.

(Associated Press)

And he made a vivid impression when he cross-examined the state’s star witness, 21- year-old Linda Kasabian, a Family member who had been present at the murder scenes. Hoping to discredit her, Hughes dwelled on her prodigious drug use, displaying a more-than-casual knowledge of the subject. His questions included:

A peyote button has fine white hairs in the middle of it, does it not?

Sometimes on grass or on hashish, don’t you see things in a totally new light?

Do you feel that you were controlled by Mr. Manson primarily by vibrations?

Did you feel that the universe was made of molecules and that somehow you fit into those molecules yourself in some perfect manner?

Hughes’ escape from Manson’s shadow — his metamorphosis from a pawn to a real defense attorney — became clear on Nov. 20, as the trial neared its end. That day, Van Houten and the two other female co-defendants, Patricia Krenwinkel and Susan Atkins, insisted on testifying.

Nobody doubted Manson’s sway over them — they would carve Xs into their foreheads in solidarity with him — and this seemed part of his plan. Maybe they would try to exonerate Manson by claiming he hadn’t ordered the murders. Maybe he just wanted a show.

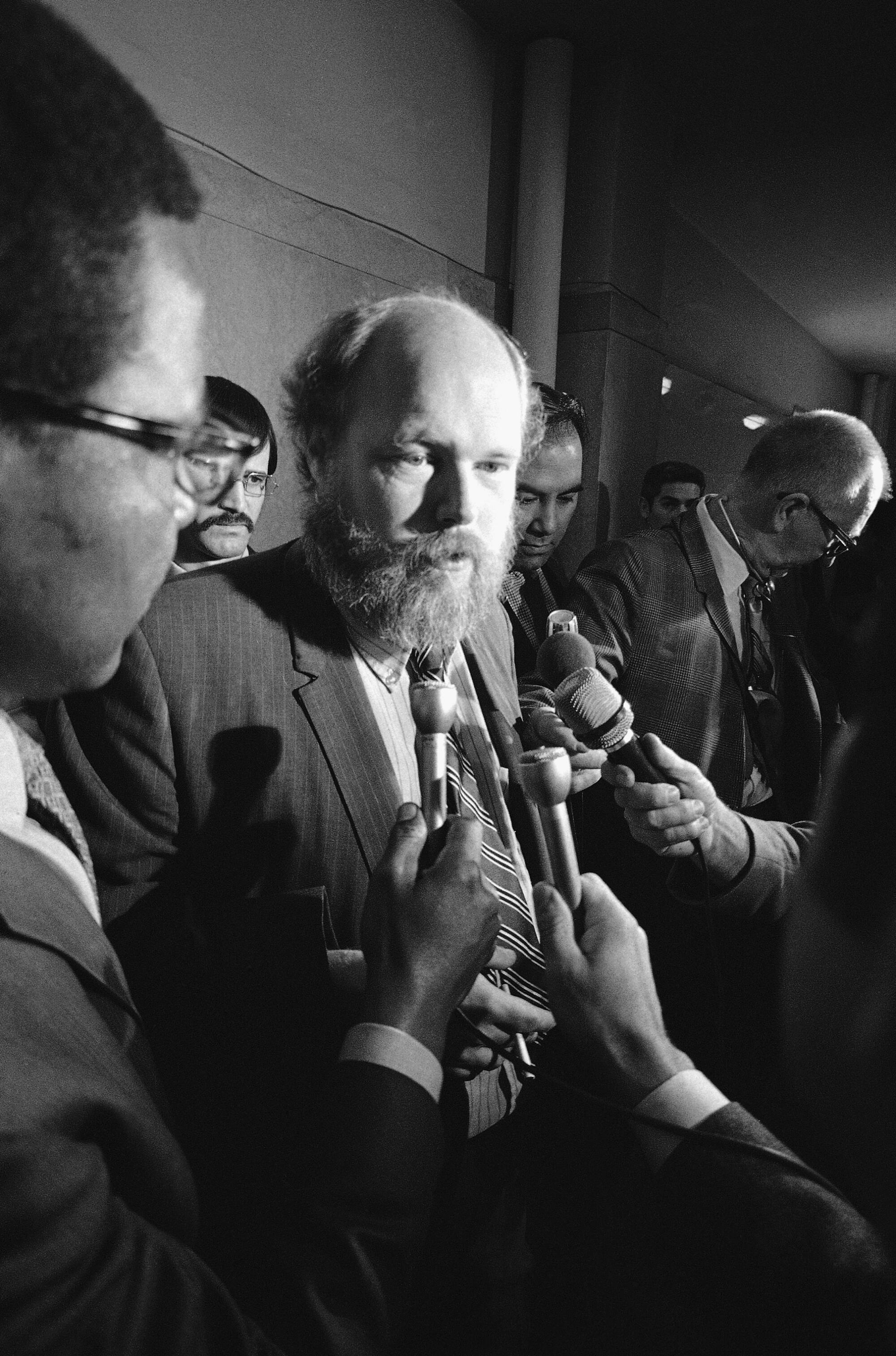

Vincent Bugliosi, lead prosecutor in the trial of Manson and three young women, wrote that his respect for Ronald Hughes grew as the trial progressed.

(Associated Press)

The judge thought they had the right to testify. Hughes thought it would wreck Van Houten’s chances. Accused of only two of the seven murders, she seemed the likeliest to be acquitted.

“Your Honor, I refuse to take part in any proceedings where I am forced to push a client out the window,” Hughes said.

Kay was sitting beside Hughes that day. He remembers Manson’s rage that Hughes was not following the script. Manson pointed across the counsel table at the hippie lawyer.

“I’ll never forget the stare that he gave,” Kay said. “He said, ‘Attorney, I don’t want to ever see you in this courtroom again.’”

The judge ordered a 10-day recess so lawyers could prepare their closing arguments. Hughes showed confidence that he could win Van Houten’s freedom.

For the break, Hughes told a reporter, he was going to a “love-in” at Sespe Hot Springs in Los Padres National Forest, a rugged area where he frequently camped. He was bringing along transcripts to study.

He caught a ride with two teenage friends in a Volkswagen, which became mired in mud as torrential rains pounded the area, creating mudslides and washed-out roads. His friends hitchhiked out. Hughes decided to stay.

When court resumed on Nov. 30, 1970, he hadn’t come back. An anonymous tipster said he was buried at the Death Valley ranch where the Manson family had lived. Police searched. He wasn’t there.

Manson demanded a mistrial, which the judge denied, and Van Houten’s newly appointed attorney scrambled to learn the case. All four defendants were convicted of murder, and Hughes remained missing.

Drew Mashburn, a retired park ranger from Ojai, told The Times he was camping in the Sespe Hot Springs area in early 1971 when he encountered a slight young woman and a gaunt young man who needed a ride.

They said they were looking for Ronald Hughes. The young woman said he was her boyfriend. They also wanted to party with Mashburn, who declined. They had Xs on their foreheads.

Four months after Hughes disappeared, trout fishermen found a badly decomposed body wedged between boulders in a remote, rocky area a few miles from Sespe Hot Springs.

Paul Fitzgerald, a Manson defense attorney, drove to the morgue to look at the body.

“Hughes had a strange-shaped head, sort of a majestic configuration, and the head is the same,” Fitzgerald told reporters.

Dental X-rays confirmed it was the missing attorney. There were no signs of foul play, but the condition of the body made it impossible to draw firm conclusions. The autopsy listed the cause of death as “undetermined.”

In his book “Helter Skelter,” lead prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi posited that it was murder, that Hughes “would pay with his life” for defying Manson. No hard evidence has surfaced to prove it, though one Manson acolyte, Sandra Good, claimed to a documentary filmmaker that the Family had killed 35 to 40 people. Hughes, she said, had been “the first of the retaliation murders.”

For people who knew the Sespe Hot Springs area, who knew how treacherous the sudden floods could be, it was possible to envision the big, ungainly man losing his footing … misjudging a river as he tried to cross … stumbling.

“Was Hughes murdered? Possibly,” Kay said. “Was he killed by a flash flood? Possibly. We’ll never know.”

Reiner can’t say either. But he remembers the sense of menace he felt when Manson’s disciples told him to quit. Maybe Hughes had received a similar order and resisted.

Maybe “they fired him the hard way.”

Sources for this story include newspaper accounts, video, transcripts of the Tate-LaBianca trial, “Helter Skelter” by Bugliosi (with Curt Gentry), and “Assassins… Serial Killers… Corrupt Cops…” by Mary Neiswender.

Source link