-

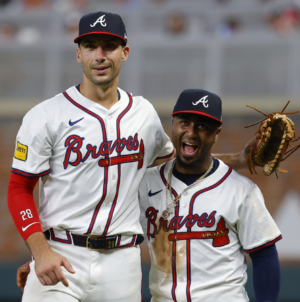

Braves Blockbuster? Ozzie Albies Involved In Shocking Trade Deadline Buzz - 29 mins ago

-

City paints over 2nd Street Tunnel graffiti. Taggers return within hours - 35 mins ago

-

NYPD Officer Killed in NYC Shooting Was Part of Paid Detail Unit - 36 mins ago

-

Washington Commanders’ Nate Herbig Makes Shocking Decision - about 1 hour ago

-

Former Football Players With CTE Have Turned to Violence - about 1 hour ago

-

Phillies Predicted To Land Two Stars In Huge MLB Trade Deadline Deal - 2 hours ago

-

UCLA to pay $6.45 million to settle suit by Jewish students over pro-Palestinian protests - 2 hours ago

-

UK Will Recognize Palestinian Statehood In September, Barring Israel-Hamas Cease-Fire - 2 hours ago

-

Blue Jays-Pirates Trade Rumors: Will Toronto Add Star Reliever? - 2 hours ago

-

Union Pacific to Buy Norfolk Southern in $85 Billion Railroad Deal - 3 hours ago

He Was Pushed in Front of a Subway Train. How Did He Survive?

Joseph Lynskey was standing on the platform of the 18th Street subway station in Manhattan, waiting for a train to take him to Brooklyn on the afternoon of Dec. 31.

He had just had lunch with friends and was headed home to get ready for a New Year’s Eve party.

Suddenly he found himself in midair above the tracks. He saw the lights of an oncoming train, so close that he could make out the shape of the train’s operator. He did not expect to survive.

“My life did not flash before my eyes,” he said. “My thought was ‘I’ve been pushed, and I’m going to get hit by the train.’”

His head, and then his body, crashed into the ground between the tracks. Blood pooled beneath his skull. The wetness, and the searing pain, let him know he was alive.

But when he opened his eyes, he saw that he was not out of danger. “I looked up, and I was underneath the 1 train,” he said.

For many New Yorkers, there is nothing quite so terrifying as the thought of being shoved into the path of an oncoming train. Mr. Lynskey survived such an attack — and he emerged with a unique perspective on a crisis that has created intense anxiety for the city’s residents, officials and tourists.

But surviving the push was only the first hurdle. Mr. Lynskey then had to find a way to get extricated from what was nearly his grave.

In New York City, the fear of crime in the subway system is not new. But in recent years — and especially since the pandemic — those fears have been amplified amid a series of high-profile random attacks on riders.

Last year, people were pushed to the tracks 26 times, including those propelled off the platform during fights. Few people shoved directly into the path of a train survive.

But then there is Mr. Lynskey.

Somehow he lived through an assault that, when viewed on video, seems unsurvivable. “A fraction of a millisecond, and that train probably would have ended my life or paralyzed me,” he said. He is not sure how to make sense of it. “I survived. I don’t know how I did.”

A suspect, Kamel Hawkins, 23, was apprehended by the police later that day. He has pleaded not guilty to second-degree attempted murder, assault and attempted assault.

Last week, Mr. Lynskey, 45, shifted uncomfortably on the couch of his sunny Brooklyn apartment, occasionally wincing in pain as he recounted with vivid detail the harrowing ordeal that left him with four broken ribs, a fractured skull, a ruptured spleen, a concussion and psychological trauma.

No one could fault him if he joined a chorus of doomsayers who condemn the subway system as a lawless labyrinth.

Yet far from disparaging his city, Mr. Lynskey, who has long been a super-user of the subway, articulated a different message: that the subway system is vital to New York’s greatness and that New Yorkers like him deserve urgent action from city and state officials who have not done enough to address the violence.

“The subway is the lifeline of this city,” he said. “I don’t think any New Yorker should have to stand against a wall or hold on to a pillar to feel safe as the train approaches.”

He added: “Unacceptable. Do better. Protect your citizens.”

Family, Madonna and tennis

Mr. Lynskey moved to New York from Miami when he was 20, packing a U-Haul and driving from South Beach to the South Slope in Brooklyn. He had been working as a music producer and quickly integrated himself into the New York nightclub and music production scenes.

He is now the head of content and music programming at Gray V, a company that creates background music and playlists for hotels, restaurants, gyms and retail businesses. (Mr. Lynskey is responsible for Carnival Cruise Line and Equinox fitness club playlists.) He still occasionally performs as a D.J. under the stage name DJ Joe Usher.

His studio apartment near Fort Greene Park is tidy and appointed to reflect his life and passions. On a bookshelf — near his favorites, which include “The Great Believers,” by Rebecca Makkai and “The Night of the Gun” by David Carr — is a photo of his parents at their high school prom, before they married and raised Joseph and his 11 siblings in Miami. A turntable and collection of vinyl are beneath the window. A tennis racket hangs from a wall, as do several photographs of Madonna. “Her music has gotten me through a lot in my life,” he said.

In 2012, after years of clubbing and partying, Mr. Lynskey quit drinking. “A life free of hangovers is one of the greatest gifts of recovery,” he said. His life is now centered on his dog, his family, work, working out, going to museums and musical performances, and travel. (After the attack, he postponed a hiking trip planned for this month to Patagonia, in South America).

A tennis obsessive since he was 8 years old, Mr. Lynskey is also an active member of Metropolitan Tennis Group, a club for LGBTQ+ tennis players and fans. “If it’s above 30 degrees,” he said, “I’ll play.”

For years he has taken the subway to public courts across the city.

‘I felt the hardest shove’

On Dec. 31, Mr. Lynskey started his day with a workout in his apartment building’s gym. He then hopped an express train to Manhattan to meet friends for lunch in Chelsea. At Da Andrea, on the corner of West 18th Street and Eighth Avenue, he enjoyed pappardelle with meat sauce and chatted for a little over an hour.

Afterward, he and Mark Murashige, one of his best friends, headed east toward Seventh Avenue. He had planned to walk to West 14th Street, to get on an express train back to Brooklyn. But at the entrance to the 18th Street station, he peered down the stairs and saw an alert that a train was coming in one minute.

Cold, he decided to take the local 1 train for one stop to 14th Street and transfer to a Brooklyn-bound express train. He hugged Mr. Murashige goodbye and bounded down the stairs.

When he reached the turnstiles, he could hear the vibrations indicating the train was making its approach. He remembers seeing no one else on the platform — no other passengers, no police officers, no Metropolitan Transportation Authority employees. He was there for perhaps 45 seconds in total, he said. He glanced quickly at Spotify on his phone but had not yet put in his earbuds.

“I could hear and see the train coming,” he said. “I probably looked at my phone for, I don’t even know, 10, 15 seconds.

“Then I felt the hardest shove,” Mr. Lynskey said. “I wasn’t braced for anyone to attack me. I’m a strong guy, but I was pushed extremely hard and from behind.

“And I flew through the air.”

He landed on his left side in the trench. His head and ribs smashed to the ground. He looked up and saw the train over him. And he glimpsed the third rail just inches away. He knew it could electrocute him if his body or even his puffer jacket touched it.

He kept himself as still as possible and began to scream: “I’ve been pushed! Someone, please, please help me!’”

He heard the voices of a man and a woman — he does not know if they were calling to him from the space between cars in the train above him, or if they were on the platform.

“She asked me if I was OK, and I started screaming that yes, I was OK, but ‘Please help me!’” he said. “She asked me my name. She asked me to spell my name. She asked me to wiggle my toes. She asked me to wiggle my fingers.”

Mr. Lynskey estimates that he was under the train four or five minutes before he heard sirens and then “absolute chaos” from the platform.

The firefighters Johnathon Aquilina and John Montalbano were among the emergency workers who raced to the scene. In a small gap between two train cars, they said in interviews, they could see Mr. Lynskey’s head, gashed and bleeding. He did not appear to be conscious.

The night before, in a drill at their firehouse, the firefighters had practiced rescuing people trapped beneath or beside a train. They knew that anyone in a subway trench risked electrocution from the third rail or the subways “shoes” — metal pieces that conduct electricity between the third rail and the train car.

They had a quick exchange with their boss about asking the M.T.A. to shut down the electricity. But then they saw Mr. Lynskey open his eyes and felt they had no time to wait.

“We had to get down there,” Mr. Montalbano said.

The firefighters lowered themselves under the train and into the trench, which was less than 10 inches deep.

“We need to get you the hell out,” Mr. Lynskey recalled their saying.

But they told him he needed to stay perfectly still. All their lives were at risk because if Mr. Lynskey touched the third rail while the rescuers were touching him, they all could be electrocuted.

“It’s very high stakes,” Mr. Montalbano said.

Once they were under the train with Mr. Lynskey, Mr. Aquilina said, “we determined that we could just drag him out quickly and kind of lift him up in between the cars.”

They dragged him by his arms for about eight feet, and then other emergency workers pulled him up onto the platform.

That is when Mr. Lynskey felt his ribs crack open.

Rescue workers sheared his clothes off him with scissors, put a brace around his neck and laid him on a board. Mr. Lynskey said he was less worried about himself than about Leo, his 16-year-old dachshund, home alone in Brooklyn.

“I’m in my underwear on the platform just begging for help,” he said. “I said to the F.D.N.Y., ‘I know I’m really hurt, but can we make sure that someone is going to be able to get to my dog?’”

Mr. Lynskey was rushed to Bellevue Hospital, where he was given a battery of tests and then questioned by the police, who told him they had arrested a suspect at a Midtown train station. His 37-year-old nephew, who had been visiting the city with his wife for the holiday, was by his bedside within an hour. Later, Mr. Murashige sat with him, and they watched from the window of the intensive care unit as the lights of the Empire State Building marked the new year.

Just after midnight, Kathleen Mank, one of Mr. Lynskey’s older sisters, walked into his hospital room. She had flown in from Florida. They both began to cry.

“It was a very rough first 24 hours,” Ms. Mank said. He was given morphine for his physical pain, but her brother’s anguish could not be dulled. “He kept repeating, ‘Why did he try to kill me?’” she said.

Three weeks later, she herself can hardly wrap her brain around the fact that her brother was pushed into train tracks, run over by a train and had lain injured just inches away from an electrified third rail.

“But he survived,” she said, “and we are so blessed that he is still here.”

‘I won’t be intimidated’

On Jan. 6, a few days after being moved from an I.C.U. to a fifth-floor hospital bed at Bellevue, Mr. Lynskey opened a news article sent to him by a friend.

It quoted recent comments made by the M.T.A.’s chairman, Janno Lieber, asserting that generating revenue was the most urgent concern of the agency and that “high-profile incidents” of violence have “gotten in people’s heads” but that “the overall stats are positive.”

“I read that while I was on Oxy after being pushed in front of a subway,” he said with audible exasperation.

Since Mr. Lynskey was pushed, other officials have weighed in. Mayor Eric Adams posted on social media that his “heart goes out to the victim,” as he praised the police response. Gov. Kathy Hochul has called for an increase in police presence during the night on subways.

He received a text message from Brad Hoylman-Sigal, the state senator for the west side of Manhattan, but no city or state leader has contacted him. “Haven’t heard a word,” Mr. Lynskey said with a shrug.

Since his release from Bellevue a week after the attack, he has been recuperating at home, working with physical therapists and welcoming a stream of visitors, who bring words of support and homemade meals.

He struggles to sleep because of his pain, but he is trying to stay positive. He is alive, and he knows more than ever how life cannot be taken for granted, how everything can change in a split second.

He has tried to avoid watching and rewatching the video of his being pushed — with limited success. When he opened TikTok two days after the attack, it was the first video the algorithm served him. “It was very disturbing,” he said.

Similarly, he does not want to talk about Mr. Hawkins, the man who was charged with pushing him. “I don’t have space or energy in my life right now to devote to anger or resentment,” Mr. Lynskey said. “He’s 23 and I don’t know much about him.”

But he will say that it is almost inconceivable to him that he — a regular New Yorker living a regular life — is the victim in an attempted homicide case. “The trauma of what I’ve experienced, it has not fully hit me,” he said. “I’m just really grateful to be able to sit here and eat a croissant.”

When he thinks back on the details of the attack, he clings to positive emotions, including pride. “I’m a survivor in a lot of ways in my life,” he said, “and I was able to remain calm and focused on making sure I got out of there in one piece.”

And he allows himself moments of humor. “When I was under the train, I thought a lot about my family and my life,” he said. “I also was thinking, ‘I guess I’m not going to Armando’s “Wicked” New Year’s Eve party.’” He laughed and then grimaced because laughing hurts his ribs.

Mostly, he is filled with gratitude toward the good Samaritans who helped keep him calm and the firefighters and other emergency workers who rescued him. He hopes for an opportunity to thank them in person one day. (The firefighters who rescued Mr. Lynskey said they were thrilled to hear that he is recuperating. “Normally when we respond to a ‘man under’ call,” Mr. Aquilina said, “the outcome is grim.”)

Mr. Lynskey believes his life was spared for a reason. “Being of service is something I really plan on focusing on for the next part of my life,” he said, though he has not yet decided in what way.

He needs to heal and then turn to his two immediate goals. He wants to get back on the tennis court by the spring. And he wants to reclaim his comfort in roaming New York.

“This city is my home,” he said, “and I won’t be intimidated. What happened to me was extremely traumatic. But I will eventually make my way back to the train.”

Audio produced by Tally Abecassis.