-

Homeless service veteran Sarah Mahin to lead new L.A. County homelessness agency - 12 mins ago

-

Minnesota Vikings Hit With Troubling J.J. McCarthy Prediction - 16 mins ago

-

Trump and Bondi, Confronted Over Epstein Files, Tell Supporters to Move On - 17 mins ago

-

Trump’s Approval Rating With Women Hits New Low in Second Term: Polls - 51 mins ago

-

L.A. business leaders frustrated by tariffs, immigration raids - 53 mins ago

-

Colorado Judge Fines MyPillow Founder’s Lawyers for Error-Filled Court Filing - about 1 hour ago

-

Donald Trump’s Approval Rating With College Students Gets a Boost—Poll - about 1 hour ago

-

Family sues over San Diego police officer found dead outside jail - 2 hours ago

-

Should New York City Ditch Its Party Primaries in Favor of Open Races? - 2 hours ago

-

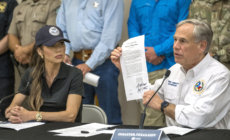

Greg Abbott Rebukes Question About ‘Blame’ As 161 Still Missing After Texas Flood - 2 hours ago

One of Hospitals’ Most Profitable Procedures Has a Hidden Cost

Cardiac surgery is a lifeline for both patients and hospitals. It’s one of the most profitable service lines in American medicine, generating an average of nearly $3.7 million in revenue per cardiovascular surgeon each year. But lurking beneath those earnings is a costly complication that’s becoming harder for hospitals to ignore: acute kidney injury (AKI).

AKI doesn’t get as much attention as other postoperative risks, like stroke or infection—but it is startlingly common. Up to 80 percent of cardiac surgery patients may have some degree of AKI associated with the procedure, according to a 2023 study published in The Annals of Thoracic Surgery.

For hospitals, that translates into longer ICU stays, higher readmission rates and up to $69,000 in additional costs per patient. In total, AKI adds $5.4 to $24 billion in complication costs to the U.S. health care system each year, researchers estimate.

It’s a stark irony, surgeons told Newsweek. The same procedures that keep hospital finances afloat are quietly draining resources through under-recognized complications.

Photo-illustration by Newsweek/Getty

“At most hospitals, one of the patients every day that you’re operating on is going to have some degree of AKI,” said Dr. Daniel Engelman, a cardiac surgeon and the medical director of the heart, vascular and critical care units at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Massachusetts. “What an unbelievable opportunity to improve patients’ lives and save money.”

The issue has gained more visibility in recent years, Engelman said. But it still isn’t a national priority—and the stakes are rising.

AKI is on a collision course with new federal reimbursement policies that could put hospitals’ already-strained margins at even greater risk. Under the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ (CMS) upcoming Transforming Episode Accountability Model (TEAM)—effective January 1, 2026—hospitals will be held financially accountable for postsurgical outcomes, including Stage 2 or greater AKI.

Engelman predicts that once hospital finance teams see how much they’re being penalized for AKI, they’ll be incentivized to minimize the “crazy number.”

“I think that’s when things will change,” he said, and “hospitals will realize that this is not acceptable.”

Why is AKI a blind spot in the first place?

It isn’t easy to change course on cardiac-surgery-associated AKI. Chronic kidney disease—a vulnerability that can heighten a patient’s risk for developing AKI—is common in the senior population that is frequently referred for cardiac surgery. But the condition can be painless, Engelman said, “Patients don’t know that they’re walking around with only half their kidney function. And even if they do, it doesn’t cause any disruption to their life until they [encounter] stress.”

That “stress” could be something unexpected, like dehydration on a beach day, or something planned, like cardiac surgery. Either way, the problem can escalate quickly.

“Suddenly, we’ve taken someone who has 50 percent kidney function down to 10 percent kidney function,” he said, “and we’re in big, big trouble.”

It doesn’t help that the current standard for AKI diagnosis is a blood test that detects a rise in serum creatinine levels. Creatinine is a waste product that is removed by the kidneys, so when kidney function drops, creatinine levels go up.

But this is a “lagging indicator” of kidney function, Dr. Kevin Lobdell, director of regional cardiovascular and thoracic quality, education and research for Atrium Health, told Newsweek: serum creatinine levels may not rise until 48 to 72 hours after the onset of AKI.

Urine output, on the other hand, is a leading indicator that can detect Stage 1 AKI about 11 hours earlier than blood tests. But manually tracking urine output is labor-intensive and error-prone, requiring bedside nurses to record data every hour. Both Engelman and Lobdell have seen it fall through the cracks in busy intensive care units (ICUs).

“We need to pay better attention to urine output, because the kidney is very smart, and when you see a tiny decrease in urine output, it’s telling you something is wrong,” Engelman said. “But you won’t know the patient’s in trouble until you watch that urine output hour by hour, very, very closely.”

Is there any technology that can improve AKI detection?

Heart function can be tracked in real time with an electrocardiogram. Lung problems can be reflected in seconds with a pulse oximeter. But since urine is the kidney’s best biomarker, its function is much harder to track.

Urine output is traditionally tracked with a Foley catheter—a device that hasn’t changed much since it was introduced in 1929, experts told Newsweek.

Catheters are common: at U.S. hospitals, one in five hospitalized patients have one at any given time. But they can also be also risky. In ICUs, 95 percent of urinary tract infections are associated with catheters, according to the International Society for Infectious Diseases.

As hospital leaders double down on quality outcomes—and reduce pressures on their nursing staff—they may be wary of increasing catheter placements.

“It is possible to work with the clinical team and nurses to closely monitor the hourly urine outputs, but in a busy unit with demanding patients, that can easily be overlooked,” Lobdell said. “Any catheter system that can facilitate the automation of the [urine] drainage as well as accounting of the hourly urine output—giving us reliable information and decreasing the demands on the staff to both be aware of and treat those threats—is incredibly valuable.”

Hospitals and electronic medical record (EMR) vendors have been working to develop better interfaces, which could continually pull data from a catheter and graph trend lines.

One company working to improve this process is Accuryn Medical. Their “smart” Foley catheter sweeps and “milks” its own line to unblock obstructions, calculates the patient’s urine output and sends that information directly to the EMR.

“This takes the manual work of milking the Foley or measuring urine completely off the nurse’s plate,” Todd Dunn, CEO of Accuryn Medical, told Newsweek.

Getty Images, Aleksandr Kharitonov

Have any health systems actually solved this problem?

In recent years, more health systems and technology companies have been working to reduce cardiac-surgery-associated AKI—but “no one system has perfected this,” Engelman said.

At his system, Baystate Health, cardiac surgery-associated AKI has drastically decreased. The organization took an “aggressive approach” to tackle the problem, and for more than seven years, it has seen half the AKI incidence predicted by the Society of Thoracic Surgeons’ database.

“A decade ago, you would always see one dialysis [machine] outside one patient room,” Engelman said. “Now, we use very, very little dialysis. It’s pretty much unheard of to come in for elective cardiac surgery and need dialysis—and that includes patients who have chronic kidney disease.”

When a patient is screened in a cardiac surgeon’s office at Baystate, they are also screened for any kidney malfunction, including baseline labs and urine output. The earlier a patient is identified as high risk, the earlier a surgeon can intervene and prevent them from developing AKI, Engelman said.

The health system has increased emphasis on pre- and postoperative care—as have Lobdell’s teams at Atrium Health. In 2023, he contributed to a literature review that outlined the evidence for “renal protective strategies.” These include holding nephrotoxic medications that could harm the kidneys, setting specific goals for urine and cardiac output and following specific protocols when those goals aren’t met.

The most important step has been counseling patients on the risks of cardiac surgery, Lobdell said, which includes performing a numerical risk assessment for renal failure: the most severe form of AKI. By discussing those risks in “simple language,” physicians and patients can engage in shared decision-making and come to an informed conclusion about whether cardiac surgery is even the right choice for them.

In 2002, Atrium Health’s renal failure rate was three times higher than the national average, according to Lobdell. By 2016, the system had “largely eliminated” renal failure.

How should health systems approach cardiac-surgery-associated AKI?

It’s not impossible to drive down cardiac-surgery-associated AKI, but it does take diligence—and now, there’s a deadline approaching. With more than 40 percent of hospitals operating at a loss, CMS’ new value-based payment models will increasingly penalize complications like AKI that prolong length of stay and drive readmissions.

Starting in 2028, hospitals will be required to report Stage 2 AKI or higher through CMS’ electronic quality measures program. Simultaneously, the TEAM model will bundle payments for certain heart procedures, making any deviation from expected outcomes a direct financial liability.

Hospital C-suites are often disconnected from care providers on the frontlines, Lobdell said. He recommends that leaders zero in on their dialysis costs from the last year, then compare length of stay and readmissions data for patients who developed AKI and patients who did not. “As we know, it’s a linear relationship,” he said.

Surgeons and their teams have a lot on their plate, and they may not realize the financial burden that AKI has on their institution—or its impact on patients’ quality of life. Once health systems have synced on the numbers, they can work to lower them, Lobdell says.

“A big take-home message I like to give cardiac surgeons is that any kidney damage—[even] Stage 1 and Stage 2 AKI—is not acceptable,” he said. “It’s not reported to our databases as a problem, yet these patients’ lifespans have been irreversibly reduced.”

“Any kidney damage is irreversible. Those nephrons are gone forever.”

Source link