-

Falcons QB Kirk Cousins Linked to 3 Potential Trade Destinations - 29 mins ago

-

What Will It Cost to Renovate Trump’s ‘Free’ Air Force One? Don’t Ask. - 51 mins ago

-

Steelers’ Aaron Rodgers Sends Clear Message to Team Icon Terry Bradshaw - about 1 hour ago

-

A Boston Suburb Removed Italian Flag Colors From a Street. Residents Rebelled. - 2 hours ago

-

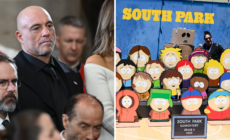

Joe Rogan Responds to South Park’s Mocking of Trump: ‘Hilarious’ - 2 hours ago

-

Phillies Trade Coming? Twins Reliever Fits What Philadelphia Needs - 2 hours ago

-

Israel Says It Has Paused Some Military Activity in Gaza as Anger Grows Over Hunger - 2 hours ago

-

Joaquin Nieman Reveals Open Reason For Axing Caddie, Coach - 3 hours ago

-

No Meals, Fainting Nurses, Dwindling Baby Formula: Starvation Haunts Gaza Hospitals - 3 hours ago

-

Texas may rig election maps. Should California too? - 3 hours ago

Point Reyes’ historic dairies ousted over environmental concerns

POINT REYES STATION, Calif. — With fog-kissed streets featuring a buttery bakery, an eclectic bookstore and markets peddling artisanal cheeses crafted from the milk of lovingly coddled cows, Point Reyes Station is about as picturesque as tourist towns come in California.

It is also a place that, at the moment, is roiling with anger. A place where many locals feel they’re waging an uphill battle for the soul of their community.

The alleged villains are unexpected, here in one of the cradles of the organic food movement: the National Park Service and a slate of environmental organizations that maintain that the herds of cattle that have grazed on the Point Reyes Peninsula for more than 150 years are polluting watersheds and threatening endangered species, including the majestic tule elk that roam the windswept headlands.

Locals in Point Reyes Station say a legal settlement that will force out historic family dairies shows no understanding of the peninsula’s culture and history.

In January, the park service and environmental groups including the Nature Conservancy and the Center for Biological Diversity announced a “landmark agreement” to settle the long-simmering conflict. The settlement, resolving a lawsuit filed in 2022, would pay most of the historic dairies and cattle ranches on the seashore to move out. The fences would come down, and the elk would roam free. Contamination from the runoff of dairy operations would cease. There would be new hiking trails. More places to camp. More conservation of coastal California landscapes.

“A crucial milestone in safeguarding and revitalizing the Seashore’s extraordinary ecosystem, all while addressing the very real needs of the community,” said Deborah Moskowitz, president of the Resource Renewal Institute, one of the groups that sued. She added that the deal “balances compassion with conservation” while also “ensuring that this priceless national treasure is preserved and cherished for generations to come.”

As news of the settlement spread, however, it quickly became clear that many in the community did not agree. In fact, they thought it showed no understanding at all of this place and its people.

A rarity for the National Park Service, the Point Reyes National Seashore has, since its founding in 1962, encompassed not just pristine wilderness but also working agricultural land. Those historic dairies have supplied coveted milk products to San Francisco for well more than a century, and today play an outsize role in California’s organic milk production. Why would anyone want to destroy one of the most preeminent areas for organic farming in the country in the name of the environment?

A sign for Historic D Ranch blows in the wind at Point Reyes National Seashore.

What’s more, the closing of the historic dairies means not just that legacy families and their cows will have to leave, but so will many dairy workers and ranchhands who have lived on the peninsula for decades. An entire community, many of them low income and Latino, are poised to lose their jobs and homes in one fell swoop.

In the weeks since the settlement was announced, there have been a spate of heated community meetings. At least two lawsuits, one from tenants being displaced and one from a cattle operation, have been filed.

“It’s a big blow to the community,” said Dewey Livingston, who lives in Inverness and has written extensively about the history of Point Reyes. He said he believes the environmental harms wrought by the cows have been exaggerated. And moving the cows out, he said, will irreparably harm the local culture. “It will turn what was once a rural area into a community of vacation homes, visitors and wealthy people.”

Environmental groups say they are sympathetic to these concerns, but that it is the duty of the National Park Service to protect and preserve the land — and that the land is being degraded.

“This degree of water pollution, which threatens aquatic wildlife habitat and public health, shouldn’t be happening anywhere, and definitely not in a national park,” said Jeff Miller, of the Center for Biological Diversity.

“If you listen to the rancher narrative, it makes it sound like ranching has always been this environmentally sustainable activity that serves all,” said Erik Molvar, of the Western Watersheds Project, another of the groups that sued. “But what we’re seeing was this herd of elk, locked up, having massive die outs. We had severe water pollution, some of the worst water pollution in California.”

A road leads to Historic C Ranch at Point Reyes National Seashore.

About 20 miles north of the Golden Gate Bridge, the Point Reyes Peninsula rises up, a paradise of ocean, dunes, cliffs and grassland that feels delivered from another time and place. Whales and elephant seals glide through the shimmering water, while bears and mountain lions patrol the misty headlands. There are pine forests, waterfalls, wildflowers and more than 50 species of endangered or threatened plants, along with the colorful flickers and chirps of more than 490 species of birds. And, of course, there are thousands of acres of green and golden hills, their grasslands softly rolling in the coastal breeze.

Intensive dairy ranching began here more than 150 years ago, spawned by the Gold Rush population explosion in San Francisco.

By the late 1850s, two brothers, Oscar Lovell Shafter and James McMillan Shafter, had established a large operation to produce butter and cheese, and ferried their goods to San Francisco on small schooner ships. By 1867, Marin County was producing more butter than anywhere else in California: 932,429 pounds a year.

Bob McClure’s ancestors arrived in 1889. His great-grandfather emigrated from Ireland and worked on the dairies. In 1930, the family acquired a ranch known — as are almost all the ranches on Point Reyes — by a letter.

“The I ranch,” McClure said. “I grew up here my whole life.” Like his father and grandfather before him, he watched over his cows as the fog rolled in and out over pastures that stretched from the hills to the sea. It was relentless work.

“The cow has this; the cow has that,” McClure explained, “and out of bed you go.” And yet, he loved it.

Historic C Ranch is seen from a hillside at Point Reyes National Seashore.

As the decades went by, other immigrant families, many of whom started out as dairy workers, purchased land from the remnants of the Shafter dairy empire. The Nunes family came in 1919. The Kehoe family took over the J Ranch in 1922. Eventually, the area became a mecca not just for milk and butter, but also for some of the fanciest cheeses in America: Cowgirl Creamery with its Mt. Tam brie and Devil’s Gulch triple cream; Point Reyes Farmstead Cheese Co., with its blue cheese and Toma; Marin French Cheese Co., with its Rouge et Noir camembert.

Over the decades, other entities also had eyes on the peninsula. By the late 1920s, developers had swallowed up much of the Eastern Seaboard and were pursuing properties on the Pacific and Gulf coasts. Conservationists pushed to preserve Point Reyes, worried it would be recast as yet another coastal resort, with hotels and arcades marching along the shoreline. In 1935, an assistant director of the National Park Service recommended that the government buy 53,000 acres on Point Reyes, but the purchase price of $2.4 million was considered too steep.

The dream persisted, and in 1962, thanks to a boost from President Kennedy, the Point Reyes National Seashore was authorized, with land purchases continuing through the early 1970s.

A view of the Point Reyes Lighthouse.

Today, the park encompasses about 70,000 acres, and is visited by about 2 million people a year. But woven into its creation was an understanding that the livestock and dairy operations would be allowed to continue.

Under an agreement with the Department of the Interior, ranchers conveyed their land to the federal government and in exchange were issued long-term leases to work that land. For many visitors, the cows — quiet herds of Devons, Guernseys and Jerseys happily munching on the flowing grasses — are just one more piece of the picturesque landscape.

But behind the scenes, tensions were brewing almost from the beginning.

McClure was only 10 years old when the park was created, so he wasn’t aware of the legal intricacies. But he recalls that his family wasn’t wild about the sale.

“Nobody really wanted to,” he recalled, but the government “could have eminent-domained it,” so the families took what they could get.

Laura Watt, a retired professor of geography at Sonoma State University whose book, “The Paradox of Preservation: Wilderness and Working Landscapes at Point Reyes National Seashore,” chronicles the history, said many of the old ranching families were discomfited by the notion of their home becoming a wilderness playground.

A cow eyes a visitor at Historic C Ranch at Point Reyes National Seashore.

The families, she noted, were “a freakish embodiment of the classic American dream.” Most had come to the U.S. as immigrants, worked as tenant farmers for the Shafter dairy empire, and eventually managed to buy land and make a go of it, passing their enterprises on to their children.

Then along comes the federal government, saying their land should be set aside as a park. “That was part of what rubbed them the wrong way,” Watt said. The ranching families had “worked so hard to be able to get this land and take care of this land” and now suddenly it was “for other people to go and play?”

Enter the elk. In the late 1970s, the government moved a dozen or so tule elk to Tomales Point at the northern end of the peninsula. The animals had once roamed the area before being hunted to extinction there; scientists were seeking to reestablish the species.

At first, the arrival of the giant mammals was not terribly controversial. The herd was small, and stayed at the top of the peninsula, where a long strip of land juts into the water between Tomales Bay and the Pacific Ocean.

Tule elk fight in a pasture at Point Reyes National Seashore.

Before too long, however, the herd multiplied, eventually outgrowing its range on Tomales Point. Some animals were moved south, where they began to compete with cows for pasture.

Even as the elk moved in, many ranching families were beginning to chafe at what they said was government red tape that made it hard to run their operations. “They will force us out with all the paperwork we have to fill out,” one rancher, Kathy Lucchesi, complained to the Los Angeles Times in 2014. “By the time they approve a project it’s too late.”

Still, the park service superintendent at the time, Cicely Muldoon, insisted the agency was committed to maintaining the ranches. “The park service has always supported agriculture, and will continue to do so,” she said in 2014.

Ranchers and the park service discussed updated leases, which would enable the ranches to make investments and long-term plans.

Environmentalists, however, were aghast, especially after word spread that the park service planned to shoot some of the elk to curb the population.

In 2016, three groups — the Resource Renewal Institute, the Center for Biological Diversity and the Western Watersheds Project — filed a lawsuit, asking a federal judge to require the park service to prepare a new general plan for the seashore, one that analyzed “the impacts of livestock ranching on the natural and recreational resources.”

The suit alleged that the ranching operations were harming coastal waters, and cited examples from the park service’s own studies that found fecal pollution in some areas. The suit alleged a long list of harms. Among them: degradation of salmon habitat; threats to the habitat of the California red-legged frog, Myrtle’s silverspot butterfly and western snowy plover; plus, members of the public reported “unpleasant odors” from the cows and their manure.

In 2017, the park service settled the suit by agreeing to draft a new plan, which it did in 2021. That plan offered ranchers new long-term leases. The park service said it would authorize the culling of elk herds, to keep them separate from the cows.

In 2022, the same groups that sued in 2016 filed suit again, this time challenging the park’s new management plan.

Molvar, of the Western Watersheds Project, said the groups feared an environmental catastrophe.

“We had cattle pastures where the native grasslands had been so completely destroyed only the invasive species survived,” he said. Combine harvesters had been spotted mowing over baby deer and baby elk. He said he had seen videos that showed flocks of ravens hovering behind the harvesters so they could “feast on the carnage.”

“The national seashore, from an ecological standpoint, was a train wreck,” he said.

After the lawsuit was filed, the park service and environmental organizations entered discussions. Eventually, the Nature Conservancy, which was not a party to the suit, agreed to raise money to try to buy out the dairies and ranching operations. The amount has not been officially disclosed, but is widely reported to be about $30 million. The parties involved are barred from discussing financial details because of non-disclosure agreements.

Many ranchers reached by The Times said they were heartbroken, but felt they had no choice but to capitulate, because it had become too difficult to continue operations.

People stroll through the Cypress Tree Tunnel in Inverness.

On Jan. 8, the parties announced the settlement, and said the ranchers, their tenants and workers would have 15 months to move out. Two beef cattle operations would be permitted to stay in the park and seven ranches would remain in the adjoining Golden Gate National Recreation Area.

“It’s very hard,” said Margarito Loza Gonzalez, 58 and a father of six, who has worked at one of the ranches for decades and now wonders how he will support his family. He added that it feels as though the people who crafted the settlement “didn’t take [the workers] into account.”

The settlement contains some money to help workers and tenants make the transition; it has been reported to be about $2.5 million, but many in West Marin think that is insufficient to replace people’s homes and livelihoods.

Jasmine Bravo, 30, a community organizer whose father worked at a dairy and who lives with her family in ranch housing, has been organizing tenants facing displacement. “This huge decision that was going to impact our community was just made without any community input,” she said.

“They thought we were going to be complacent and accepting,” she added. But “there are tenants and workers who have been here for generations. We’re just not going to move out of West Marin and start over. Our lives are here.”

On March 11, the Marin County Board of Supervisors voted to declare an emergency shelter crisis to make it easier to construct temporary housing for displaced workers. Many residents showed up to applaud it — and also to say it wasn’t nearly enough.

Albert Straus, whose legendary Straus Family Creamery sources organic milk from two of the local dairies, said that the organic operations in Marin and Sonoma counties “have become a model for the world,” and that the ousted dairies are family operations that worked in concert with the community and the land.

He recently published an op-ed calling on the Trump administration to reverse the decision. “The campaign to displace the ranchers reflects a misguided vision of nature as a pristine playground suitable for postcards and tourists, with little regard for the community or the planet,” Straus wrote.

In an interview, he said that the issue feels “very raw, and we’re trying to change that direction to save our community, our farms and our food.”

He added: “I never give up.”

Source link