-

The Resurrection of Trump’s Support for Pete Hegseth - 13 mins ago

-

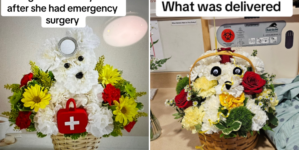

Woman Orders Flowers for Sister in Hospital—Hysterics Over What Arrives - 21 mins ago

-

Winds drop, chance of rain as fire danger ebbs in Los Angeles - 27 mins ago

-

Should You Vacation in South Korea? Experts Weigh In Amid Political Unrest - 56 mins ago

-

Man Found in Syria Appears to Be Missing American - 57 mins ago

-

Official says L.A. County may defy state order to close juvenile hall - about 1 hour ago

-

Will Joe Biden Pardon Hillary Clinton? Bill Clinton Weighs in - 2 hours ago

-

Can Psychedelics Help CEOs Boost Their Leadership Skills? - 2 hours ago

-

The UnitedHealthcare killing won’t improve insurance. This would - 2 hours ago

-

Kadyrov Troops Hurt as Drones Strike Military Barracks Deep Inside Russia - 2 hours ago

The gambit to preserve a three-generation legacy of affordable rents in Cypress Park

For 15 years, it was a ritual that kept Andrés Cortes close to his beloved abuelita.

He would collect the rent from the other four tenants of her Cypress Park rental property, add his own and deliver the envelope in person to the family homestead a few blocks away.

She’d ask for news of the tenants by name and demure every time he told her they were willing to pay more.

“No,” she’d say. “I have enough.”

That unwritten contract expired in March when the widowed Rufina Cortes died at 97. Her six children faced the inevitable decision to put the five-unit property, in the family since the 1970s, up for sale.

The tenants needed a buyer who would be willing to sacrifice profit to keep the rents affordable. But to buy the property at current market rates without jacking up rents, even an altruist would have to come up with some unlikely financial wizardry.

And it wasn’t altruists showing interest. Cortes and his partner, Claire Bernson, found themselves increasingly dismayed with a string of investors and developers brought through their one-bedroom cottage on the two-lot complex.

Andres Cortes’ walks with Erika Flores who rents a place at his Cypress Park property.

(Carlin Stiehl / For The Times)

“They weren’t hiding anything,” Cortes said. “They wanted to get rid of us. While we were right in front of them, they will be talking about tearing down walls. It was dehumanizing.”

They knew how this situation normally played out in L.A.: “cash for keys” to remove the nine tenants, demolition, new construction and higher rents presaging a change of character for the prewar homes on Arvia Street, part of one of L.A.’s last neighborhoods still largely untouched by gentrification.

Other tenants had lived there longer than Cortes had. He polled them and found, not surprisingly, that they would all work with him to stay. But how?

A 39-year-old artist with no experience in finance or real estate, he had no idea.

Ultimately, it would be his art, and some luck, that provided the answer.

The last stop on a Clockshop walking tour of Cypress Park was the alley behind the Arvia Street property where Cortes has been working for 10 years creating a mosaic of broken chips of tile, mirrors and found objects.

Claire Bernson watches Richard the cat in front of Andres Cortes’ Cypress Park property in Los Angeles.

(Carlin Stiehl / For The Times)

The story of his family’s three-generation stewardship of the property — and its impending end — naturally became intertwined with the project as a autobiographical story of his bonding with the community.

As the tour was breaking up, one of the participants pointed Cortes to Betty Avila. She is a board member of LA Más, a Cypress Park-based nonprofit that seeks to build “collective power and ownership for neighborhood stability and economic resilience” throughout Northeast Los Angeles.

The chance meeting came at a perfect moment. After focusing for several years on helping Northeast Los Angeles homeowners build backyard units, LA Más was expanding into housing preservation.

“We went through a year of engagement with our community members asking, ‘What do you want to us do?’ ” said executive director Helen Leung. “They chimed in, ‘There is so much risk of displacement: A lot of residents getting kicked out; no affordable options. Can you find options to keep housing affordable for longtime residents?’ ”

Andres Cortes and Claire Bernson stand in the back alley of Cortes’ Cypress Park property.

(Carlin Stiehl / For The Times)

Ariva would be the test case with challenges. The six children of Felipe and Rufina Cortes agreed to discount the $1.5 million appraised value. But the rents of $600 to $1,000 were far too low to support financing the final price of $1.2 million.

“No way we could get money for that,” Leung said. “It didn’t pencil out. What can we do?”

Four of the five tenants, among them a couple with a teenage daughter who has lived there her entire life, volunteered to raise their own rents, but that was a not a solution either. By law, the rent-stabilized units couldn’t rise high enough to service a mortgage.

Looking over the four buildings on the property — the single family home Cortes and Bernson live in, two duplexes and an ancient tool shed refashioned as an artist’s studio — LA Más concluded the shed would have to go to make room for an ADU that would bring in market-rate rent.

With two bedrooms in a tight 640 square feet, Leung figured it would command $2,700 a month. But with each the other five units bringing in much less, that was still thin for a conventional loan on a $1.6 million project with the ADU.

The sun sets over a unit on Andres Cortes’ Cypress Park property.

(Carlin Stiehl / For The Times)

Much like developers who use tax credits to build affordable housing, Leung had to assemble financing from multiple sources. But in contrast to the complicated, competitive and time-consuming pipeline to tax credits, she called on personal relationships in a network of social impact investors.

The bulk came from the Self Help Ventures Fund, a national nonprofit that raises capital from mission-aligned organizations and individuals. It had funded LA Más’ earlier affordable ADU program.

Self Help contributed $1.22 million that will have to be repaid to its investors. Leung refers to it as debt-like equity because the rate is lower than a conventional loan and Self Help doesn’t require a fixed repayment schedule.

“Given the nature of the project, we recognize there needs to be some flexibility in the first two years while we stabilize and build the ADU,” said Tim Quinn, senior project manager at Self Help Ventures Fund. “We don’t need to see our investment returns on year one. We just need to see that over time the investment will bear fruit and be a good investment.”

A photo of Andres Cortes’ grandmother hangs on the wall inside his home on his Cypress Park property.

(Carlin Stiehl / For The Times)

Self Help added a little over $90,000 of its own funds as equity to become a co-owner of the property.

LA Más, as the managing co-owner, sought grants for its equity share, and received $250,000 from Mayor Karen Bass’ LA4LA program.

“It’s such a phenomenal idea to be able to take off the market a five-unit complex and preserve it as affordable and have no one be displaced and even build community through the process of acquisition,” said LA4LA lead strategist Sarah Dusseault. “It’s been a phenomenal experience being part of it.”

Leung finally turned to the LISC, the Local Initiatives Support Corp., a national nonprofit that raises capital for local groups.

LA LISC obtained a $40,000 grant from the U.S. Treasury Department’s CDFI Equitable Recovery Fund.

With another $40,000 grant, the funding package was complete, and escrow closed in October.

The Arvia Street purchase is part of a movement of community-based groups trying to slow displacement of low-income tenants by purchasing historically affordable housing at risk of being sold to investors seeking maximum return. There is no single model. Some use government funds. Others, under the land trust model, help tenants purchase the buildings they live in. The only constant is that it’s complicated.

Leung hopes the multi-pronged financing package she put together can be used again and again to preserve affordable housing as other projects come to their attention.

Arvia Street is now owned by an LLC controlled by LA Más and Self Help with a required component of tenant engagement.

A mutual trust developed over deep community ties.

“They were checking out us, if our values align with theirs, and we were doing the same thing,” said Bernson, who has lived with Cortes in the home since 2020.

Cortes did not grow up in Cypress Park. Priced out of Los Angeles, his parents settled in Chino Hills but returned to the old neighborhood regularly on weekends to be with aunts, uncles and cousins.

Andres Cortes’ Cypress Park property.

(Carlin Stiehl / For The Times)

Cortes would often walk from the homestead to Arvia to find his abuelito in the shed out back doing maintenance or puttering at his TV and radio repair business.

In 2009, the front house became vacant, and Cortes, in his senior year at Cal State LA, accepted his father’s offer to move in. His connection with the neighborhood grew with the mural, which now stretches hundreds of feet on the backyard walls of several neighbor’s homes and includes guest works by Bernson and other artists.

“That’s my language, my way of communicating with people,” he said. “It’s a way of meeting people in the neighborhood, working with kids.”

Cortes also had a sentimental attachment to the shed, where he and Bernson had set up their studio. For the deal to work, it would have to be razed to make room for the ADU.

“That’s a sacrifice in the mix,” Cortes said. “Yeah, whatever needs to happen. I’m willing to put that down.”

Cortes and Bernson have now assumed new roles as part of an evolving tenant governance community. They serve as the tenants’ liaison to LA Más for decisions affecting their homes, such as where the ADU will be placed and, in the future, maintenance and rent increases. They’re also attending monthly meetings of the Northeast Los Angeles Housing Alliance that advises LA Más on broader policy.

In January the organization is launching a committee that will include residents to advise it on future projects.

Cortes is uncertain what all that means for him.

“The difference is now that, for as much as I don’t know, I’m certain that the legacy of my grandparents and for this home to be for this community, that’s going to be held together.”

He still collects the rent, but now he walks it to the La Màs headquarters, five blocks away. It’s not the same as it used to be with his abuelita.

“My last conversation with her, she was getting coupons from Super King,” he said. “She was sharing how these coupons were better than other coupons.”

And she asked about the tenants.

Source link