-

Today’s ‘Wordle’ #1,283 Answers, Hints and Clues for Monday, December 23 - 9 mins ago

-

Artists We Lost in 2024, in Their Words - 29 mins ago

-

John Cena vs Logan Paul ‘On The Table’ For WrestleMania 41: Report - 44 mins ago

-

Ron Eliran, Israeli ”Ambassador of Song,” Has a Bar Mitzvah at 90 - about 1 hour ago

-

Phillies Predicted To Cut Ties With Trade Acquistion Austin Hays - about 1 hour ago

-

Mets Likely To Sign Pete Alonso Amid Depleted First Base Market - 2 hours ago

-

Trump Picks Callista Gingrich for Ambassador to Switzerland - 2 hours ago

-

NASCAR Cup Series Team Confirms 2025 Daytona 500 Entry Plans - 2 hours ago

-

Trump Names His Picks for Top Pentagon Roles - 3 hours ago

-

The IRS might be dropping $1,400 into your stocking this year - 3 hours ago

The reporter who brought down O.C. Supervisor Andrew Do

I greeted Nick Gerda last week the same way I’ve greeted him over the past year: a handshake, a hug and a “Great job, man.”

Since last November, the LAist reporter has dropped bombshell after bombshell about Andrew Do, a longtime politician who most recently served as an Orange County supervisor.

I say “most recently” because Do resigned after federal prosecutors announced he would plead guilty to accepting over half a million dollars in bribes to direct more than $10 million in COVID-19 relief funds to a nonprofit headed by his college-age daughter, Rhiannon.

“The scheme essentially functioned like Robin Hood in reverse,” U.S. Atty. E. Martin Estrada said at a news conference on Oct. 22.

Estrada credited the media for breaking the story — which really meant Gerda, who used to affix mics to my shirt when he was an intern at Orange County’s PBS channel about 15 years ago.

And look at him now!

He’s like Clark Kent with peach fuzz: tall, slender, soft-spoken, favoring khakis and long-sleeved shirts and more earnest than a Peace Corps volunteer. We met at my wife’s store in downtown Santa Ana, not far from where the Board of Supervisors meets, so I could offer congratulations again — and not just for ending the career of a politician who was as insufferable as the bow ties he wore.

Gerda’s career is an exemplar of what happens when news organizations invest in local journalism, let reporters dig instead of writing clickbait and stand by them in the face of critics real and imagined.

For over a decade with LAist and his previous employer, Voice of OC, Gerda reported on Do the way a sculptor works a slab of marble. His torrents of public records requests led the supervisor to derisively refer to “the Noise of OC.”

Last year, Do demanded that LAist fire Gerda for allegedly using falsified tax returns in his reporting, a tantrum that went nowhere because it wasn’t true. Days before FBI and IRS agents raided the homes of Do and his daughter, the politician appeared on a Little Saigon radio station to accuse Gerda and other opponents of “slander.”

“On the one hand, I feel vindicated,” the young reporter — just 33 — told me as we drank coffee, the strap on his digital watch half torn. “On the other hand, this is the worst concern I had looking into this: what happened with this money.”

Do’s misdeeds were so egregious that Gerda did the impossible in Orange County: unite Democrats and Republicans.

I asked Gerda why he thought the Do matter bridged O.C.’s partisan divide.

“People perceive that as an abuse of power,” he replied, “and that really connects with people, makes them concerned.”

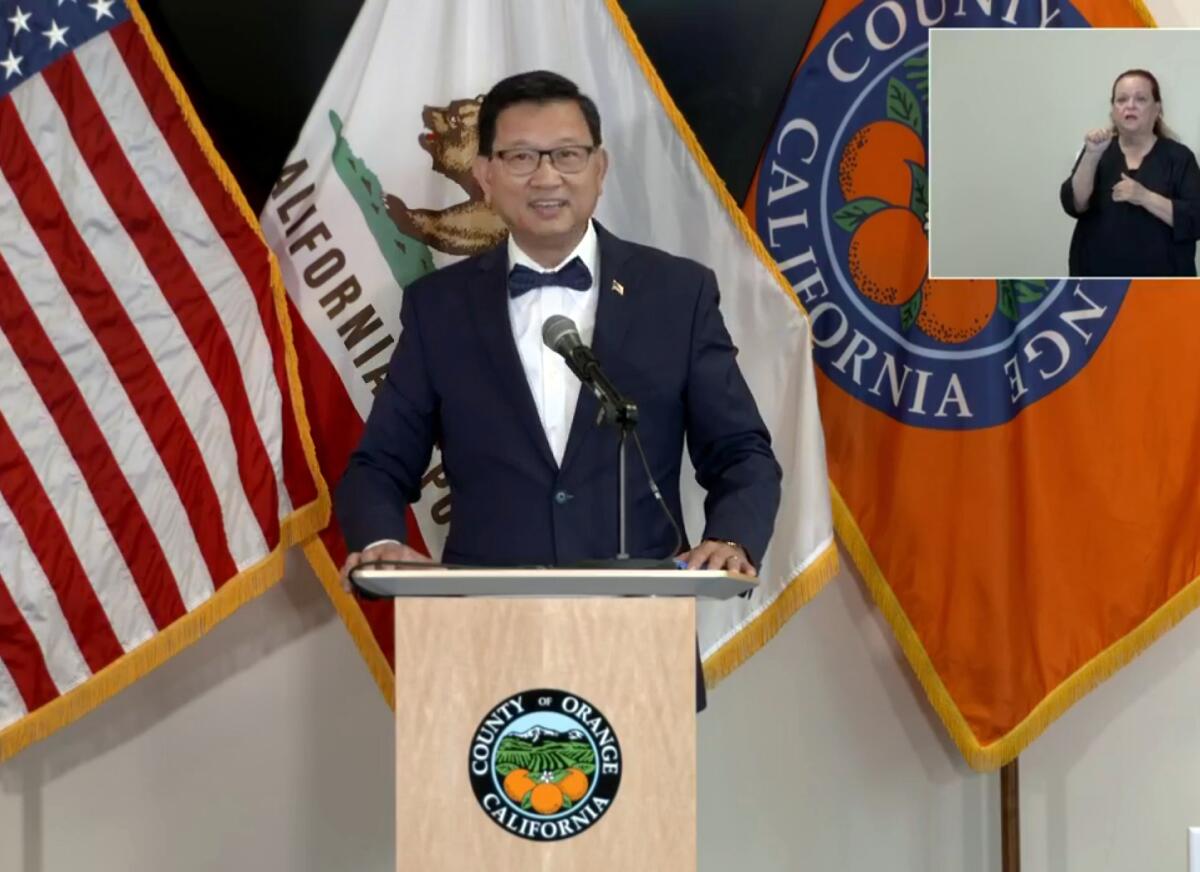

Former Orange County Supervisor Andrew Do, pictured during a 2021 news conference in Orange, has pleaded guilty in a bribery case that a U.S. attorney called “Robin Hood in reverse.”

(Lilly Nguyen / Daily Pilot)

Local journalism was in the stars for Gerda long before he pursued it. He accompanied his mother to Santa Ana City Council and school board meetings as a teenager, when I was starting out as a reporter and found her generous with quotes, insights and tips.

“My parents showed me how journalists have a really important role in society to seek the truth,” Gerda said. “Speak truth to power when there’s abuses going on.”

Journalism stayed on his mind after he earned a bachelor’s degree in political science from UC Irvine at just 18 and studied afterward at NYU and in Cairo while considering international relations as a career.

In the late aughts, Gerda noticed that news organizations in Southern California were laying off reporters who “were keeping an eye” on local government.

“I knew from seeing my parents and following local news when I was growing up that people have a real ability to make a positive difference in their local community in a way that’s just impossible oftentimes at the national or international level,” he said.

Gerda returned home and enrolled in journalism classes at Orange Coast College, where I teach. After a few internships, he found a job at Voice of OC, where he immediately caught the attention of publisher Norberto Santana Jr. The nonprofit news agency’s founder said he drilled into Gerda to treat local reporting “like electrical work, like plumbing — a methodical approach. Follow the money. And he was just solid from the start.”

Santana Jr. put the cub reporter on the county government beat, which is how he found himself at Do’s election night party in 2015, the first time Do ran for supervisor. Gerda’s clearest memory of that night: Do berating another Voice of OC reporter to the point that Do’s supporters had to hold him back.

“It stood out to me as the kind of behavior towards a member of the press that I wasn’t used to,” Gerda said.

The new supervisor immediately gave Gerda material to report on. There were questions about where he actually lived, and he unsuccessfully pursued a policy to shut down public commenters he deemed offensive. His office used voter data to send out taxpayer-funded mailers, which spurred the state Legislature to ban such efforts within 60 days of an election.

None of that derailed Do’s career — he kept winning elections, becoming chair of the Board of Supervisors in 2021.

I asked Gerda why Do got away with things for so long.

Gerda mentioned a 2013 Orange County grand jury report that said the lack of a vibrant press in O.C. was essentially an invitation for civic corruption, which has sadly proved true.

The only publications that regularly cover a county of 3.1 million people are the Voice of OC, the Daily Pilot and the Orange County Register, which is a ghost of what it once was.

The mayor of Rancho Santa Margarita and a City Council candidate in Fullerton recently pleaded guilty to filing false affidavits attesting that they had personally collected and witnessed signatures on their nominating papers. In my hometown of Anaheim, an ongoing federal investigation has led to the resignation of former Mayor Harry Sidhu, who pleaded guilty to four felony counts for his role in a proposed sale of Angel Stadium to its namesake baseball team.

Orange County “struck me as a place where a lot of elected leaders, compared to places like L.A., were not subject to, or used to, as much media scrutiny and attention and questions,” Gerda continued. “And a lot of things that perhaps would be questioned and noted in a place like L.A. go on unnoticed by the public.”

Gerda largely left Orange County politics behind when he joined LAist last spring to cover homelessness in L.A. County. That’s why he took a month to return a call from a source alerting him to the Viet America contracts — “I almost missed this tip, actually,” he sheepishly admitted.

State Sen. Josh Newman (D-Fullerton), left, congratulates LAist reporter Nick Gerda on his work.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

After reviewing thousands of pages of documents, Gerda published a story in November detailing how Do voted to award millions of dollars in county contracts to the Viet America Society without revealing it was headed by his daughter, Rhiannon.

Gerda followed days later with another bombshell: The supervisor’s testimony in a civil lawsuit had led to a mistrial because he failed to disclose that his wife, Cheri Pham, was an assistant presiding judge in the same courthouse.

As a result of Gerda’s drip-drip of stories, Pham announced she wouldn’t seek reelection, the county sued the Viet America Society for “brazenly plunder[ing]” more than $13 million and Gov. Gavin Newsom signed a bill banning elected officials from approving contracts for organizations headed by their children.

Gerda wouldn’t speculate on whether his reporting was the catalyst for the federal investigation into Do. This week in federal court, the former supervisor pleaded guilty to one count of conspiracy to commit bribery concerning programs receiving federal funds.

“It’s true. I have great sorrow for my actions,” Do said at the hearing. “I’m responsible for every word.”

Do faces a maximum of five years in federal prison. Meanwhile, Rhiannon Do has agreed to three years of probation and a diversion program, in addition to assisting the feds in their continuing investigation and giving up a million-dollar home in North Tustin that prosecutors allege she knowingly bought with federal funds meant to feed elderly Vietnamese refugees.

So who is Gerda taking down next?

For the first time all morning, he laughed.

“I don’t think of it as taking down people,” he said. “There’s a number of other funding streams and questions out there about taxpayer money that was meant to serve vulnerable people.”

He got up to drive back to work.

“And we are continuing to pursue the truth.”

Source link