-

Maurice Jones-Drew Down on Consensus Top Running Back Prospect in NFL Draft - 21 mins ago

-

Declassified JFK assassination files released by Trump administration - 25 mins ago

-

Pod of Dolphins Greets NASA Astronauts After Splashdown - 30 mins ago

-

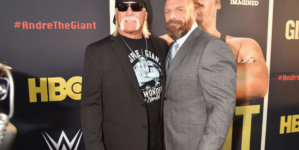

WWE Drastically Cuts Price of Hulk Hogan WrestleMania VIP Experience - 56 mins ago

-

‘I helped elect her’: Protesting Medi-Cal cuts at O.C. rep’s office - about 1 hour ago

-

Judge Blocks Policy That Would Expel Transgender Troops - about 1 hour ago

-

Trump Contradicts Kremlin, Denies Discussing Halt to Ukraine Aid With Putin - 2 hours ago

-

Did Trump Officials Defy a Court Order? - 2 hours ago

-

NFL Mock Draft 2025: Predicting the Entire First Round - 2 hours ago

-

Braves to Sign Craig Kimbrel to $2 Million Contract: Report - 3 hours ago

Volunteers race to save vintage tiles from bulldozers in Altadena

The team of masons, covered in dust and sweat, had been working in the ruins of the Altadena house for hours when a shout echoed across the wreckage.

Volunteer Devon Douglas emerged from a pit of rubble that had once been the living room, staggering under the weight of a concrete slab more than a foot wide.

“It’s a stair,” Douglas said, turning toward homeowner Valerie Elachi. “A whole stair, and all the tiles.”

It was a bittersweet moment for Elachi, 76, who had danced down that tiled staircase when she and her husband first saw the home during an open house in the early 1980s.

She watched from her patio wall as five volunteers chiseled the historic tiles from the stairs and from her massive living room fireplace. Having something to salvage was a gift, she thought, and a bitter reminder of all they had lost.

Cliff Douglas uses a chisel to gently remove historic Batchelder tiles from the fireplace of a 1923 Altadena home built by noted local architects Myron Hunt and Elmer Gray.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

The work on Elachi’s home was being done by a ragtag group of volunteers who call their collective Save the Tiles. The group is racing to remove and preserve thousands of vintage and historically significant tiles from the Eaton fire burn zone before the properties are bulldozed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

As part of their work to remove debris and level lots for rebuilding, the Army Corps tears down everything left standing on a property. That includes chimneys and fireplaces, which can be left structurally weakened by fire.

“Anything you haven’t removed is gone forever,” said Eric Garland, one of the Save the Tiles organizers.

The volunteers have preserved the tiles from about 50 homes, and have about 150 left on their list. Already, they’ve had one close call, removing the tiles from one home just two days before the Army Corps arrived.

Finding enough skilled masons was the group’s first challenge. Now, their biggest hurdle is tracking down the homeowners and getting their permission to remove tiles from their properties.

A team of volunteers is using public records to trace homeowners, but they’re hitting a lot of dead ends. Property records generally don’t contain any contact information, and when they do, the phone numbers are often out of date. In some cases, the numbers ring to landlines that burned down.

“There will be a day, soon, when we wake up and there are no houses in our queue,” Garland said, “even though we know there are dozens left.”

The Batchelder tiles removed from Valerie Elachi’s fireplace were placed in a cardboard box before being cleaned and packed for long-term storage.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

The group’s last-ditch effort to reach homeowners is a letter. Mail is still being forwarded, Garland figured, so maybe it was worth a shot.

“Dear displaced neighbor,” the letter begins. “… We are just volunteers and Altadena neighbors desperate to reach you because we want to rescue your historic fireplace tiles for free. That’s it. No strings. Just trying to save what’s left of beautiful Altadena and bring some joy.”

:::

Garland embarked on the tile rescue mission after a walk through Altadena with his teenage daughter.

Their house survived the Eaton fire, but many on their street did not, including their neighbor Fred’s 1924 Spanish-style house. Amid the rubble, they spotted his century-old fireplace, its gray, brown and beige tiles still intact.

“That beautiful fireplace is all they have left,” Garland’s daughter said.

Garland emailed the neighborhood list-serv to ask whether anyone was saving the tiles. One response sent him to Douglas, who had written on Reddit that her father, Cliff, a professional mason, was volunteering to remove tiles from ruined homes for free.

The teams joined forces. In early February, they gathered dozens of volunteers in the parking lot of an Aldi grocery store in Altadena. Garland and fellow volunteer organizer Stanley Zucker handed out printed maps of the burn zone and sent small groups out on foot, telling them to stick to the sidewalks and photograph any tile that looked remotely historic.

In two days, the volunteers completed an ad-hoc architectural survey of thousands of burned properties. They whittled down the list to more than 200 homes with Arts and Crafts tile, many by the famous Pasadena artisan Ernest Batchelder and one of his main competitors, Claycraft.

First produced on the banks of the Arroyo Seco in 1910, Batchelder tiles were a key part of the California Arts and Crafts movement, a return-to-nature style that was a response to the ornate designs of the Victorian era and the industrialization of American cities.

Most Batchelder tiles are in private homes, but they can also be found on the Pasadena Playhouse’s courtyard fountain, the floors of Pasadena’s All Saints Episcopal Church and the lobby of the downtown Los Angeles Fine Arts Building on 7th Street. (One of his largest surviving commissions, the 1914 Dutch Chocolate Shop in downtown, is generally closed to the public.)

California in the early 20th century was rich with clay and with cultural influence, said Amy Green of Silverlake Conservation, a firm that repairs and restores historic tile. In addition to the Arts and Crafts movement, tile artists began producing a wide variety of works inspired by traditional Mexican and Indigenous designs, as well as European styles like Delft.

Devon Douglas, daughter of professional mason Cliff Douglas, inspects a Mayan-style Batchelder tile that had just been removed from a fireplace.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

“It reflects who and what we are,” Green said. “A very interesting mix of people that bring different aesthetics and skills to our work.”

Batchelder tiles can be palm-sized or larger, with muted matte finishes and understated glazes. A company catalog from 1923 described the tiles as “luminous and mellow in character, somewhat akin to the quality of a piece of old tapestry.”

They could be ordered through a catalog and were relatively affordable, said Anuja Navare, the director of collections at the Pasadena Museum of History, which maintains a private registry of homes with Batchelder tiles. Many middle-class families splurged a little and installed them in new bungalows in the 1910s and 1920s.

“He made beauty available to a person with modest means,” Navare said.

The work of Batchelder and his competitors spread to thousands of homes, businesses and civic institutions across Southern California.

American tastes changed, and, by the end of World War II, many of the tile companies had gone under. Arts-and-crafts tiles were painted over or ripped out in favor of the avocado greens and burnt oranges of the 1970s.

But the tiles have come back into vogue in the last two decades and have developed a cult following among design enthusiasts. Actress Diane Keaton has renovated entire homes with historic tiles, and preservationists have been known to dumpster dive to save Batchelder tiles from the landfill.

A single salvaged tile can sell for more than $200. A fully intact hearth and mantle can fetch 100 times that.

Early on, the Save the Tiles group was on high alert for looters in the burn zone. Most people would drive past the ruins of a home without a second look at the fireplace, but a select few know what to look for.

Cliff Douglas, the mason, said he had assessed several fireplaces along one street and returned to find the tiles gone. It was impossible to know, he said, whether the tiles had been removed by the homeowners or by someone else.

The group tackled the most visible fireplaces first, including those on corner lots. One volunteer with Hollywood set-building experience built false fronts to disguise fireplaces as any other fire debris.

The tiles must be removed by trained masons, and Save the Tiles now has four crews ready every day, made up of volunteers and workers whose employers are covering their wages. The group plans to start paying the masons from a GoFundMe that has now raised more than $100,000.

Cliff Douglas inspects a historic fireplace covered in Batchelder and Grueby tiles.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

About 20 volunteers learned from Green how to properly clean, catalog and store the tiles. Some cracked tiles will still need to be professionally restored, which will cost money, but a lot of the work can be done by amateurs, Garland said.

Some of them are sitting in boxes on a side porch at Garland’s mother’s house, and others are in a climate-controlled warehouse in Harbor City donated by a friend in the tile industry. The tiles will wait until homeowners are ready to take them back.

The power of the project, Green said, is that the hearth has such importance in the home: “It provides warmth,” she said. “It’s where you gather.”

:::

Despite the pressure of the bulldozers moving closer, removing the tiles is delicate work that can’t be rushed.

On a recent weekend, ceramicist Jose Nonato stood in the rubble of a three-bedroom home along East Altadena Drive, his hair, forearms and apron coated in dust. The third-generation ceramicist from Mexico City saw a Facebook post about the rescue effort and showed up with his tools. He had been working for hours in the sun on his 30th wedding anniversary to extract tiles surrounding a fireplace.

The tiles had been fired once, a hundred years ago, in kilns that reached 2,200 degrees Fahrenheit, Nonato said. He said the Eaton fire had thrown them into thermal shock. They could crumble at any moment.

Nonato laid his chisel against the mortar and gingerly began to tap the top of the tool with a hammer. He gently pried loose a tile the size of a paperback book and wiped his hand across the dusty surface. A faint green hue shone through — a Batchelder.

By the end of the day, Nonato had rescued about 90% of the tiles and laid them on a blanket in the driveway in the same pattern as the fireplace. A few were broken and held together by red duct tape, but those would be repaired. Soon, the tiles would be cleaned, boxed and stored for the homeowners, who planned to rebuild.

“This is basically the only thing still left,” Nonato said. “This, and memories.”

:::

Elachi, the Altadena homeowner, had initially hoped that the tile volunteers could shore up the massive Batchelder fireplace in her living room so the home could be rebuilt around it.

From left, Cliff Douglas and his assistants Martin Vargas, Jorge Vargas and Roberto Murillo remove debris from the hearth of a home in Altadena.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

To her disappointment, Cliff Douglas told her that the mortar had been weakened in the fire. Everything would have to come down, he said, or the Army Corps would take it down themselves.

Elachi and her husband raised their daughter in the 1923 Pueblo Revival-style home and spent four decades caring for the property, embracing its Southwestern style and finding furniture and art that, along with the pink adobe walls and wood beams above the windows, would have looked at home in Santa Fe.

“This house was like another child to us,” Elachi said.

The fire had taken almost all of it: her husband’s memorabilia from 15 years as the director of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, their ceramics and furniture, all their photographs and books. The loss felt overwhelming and enraging. They hope to rebuild, but aren’t sure yet whether they will.

Source link