-

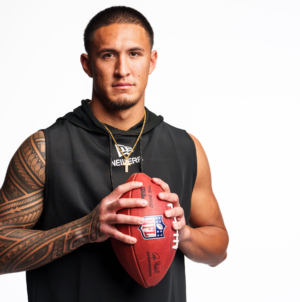

How to Buy Tetairoa McMillan Carolina Panthers Jersey - 21 mins ago

-

Opinion | Trump’s Single Stroke of Brilliance - 30 mins ago

-

How to Buy Travis Hunter Jacksonville Jaguars Jersey - 56 mins ago

-

Trump’s Crimea Proposal Would End a Decade of U.S. Resistance - about 1 hour ago

-

NFL Draft 2025: Shop the Official Draft Hats by Team - 2 hours ago

-

Salinas produce supplier accused of causing E. coli outbreak - 2 hours ago

-

Why Did a Charity Tied to Casey DeSantis Suddenly Get a $10 Million Boost? - 2 hours ago

-

Trump Admin Cuts Time for Migrants to File Deportation Appeal In Half - 2 hours ago

-

Rabid bat found in Orange County, health officials say - 2 hours ago

-

Trump Signs Order to Establish US ‘Dominance’ in Seabed Mineral Mining - 3 hours ago

Trump Takes a Major Step Toward Seabed Mining in International Waters

President Trump has ordered the U.S. government to take a major step toward mining vast tracts of the ocean floor, a move that nearly every other nation in the world considers off limits to this kind of industrial activity.

The executive order, signed Thursday, would circumvent a decades-old international treaty that every major coastal nation except the United States has ratified. It is the latest example of the Trump administration’s willingness to disregard international institutions and is likely to provoke an outcry from the country’s rivals and allies alike.

The order “establishes the U.S. as a global leader in seabed mineral exploration and development both within and beyond national jurisdiction,” according to a text released by the White House.

Mr. Trump’s order instructs the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to expedite permits for companies to mine in both international and U.S. territorial waters.

Parts of the ocean floor are blanketed by potato-size nodules containing valuable minerals like nickel, cobalt and manganese that are essential to advanced technologies that the United States considers critical to its economic and military security, but whose supply chains are increasingly controlled by China.

No commercial-scale seabed mining has ever taken place. The technological hurdles are high, and there have been serious concerns about the environmental consequences.

As a result, in the 1990s most nations agreed to join an independent International Seabed Authority that would govern mining of the ocean floor in international waters. Because the United States isn’t a signatory, the Trump administration is relying on an obscure 1980 law that empowers the federal government to issue seabed mining permits in international waters.

Many nations are eager to see seabed mining become a reality. But until now the prevailing consensus has been that economic imperatives shouldn’t take precedence over the risk that mining could damage the fishing industry and oceanic food chains or could affect the ocean’s essential role in absorbing planet-warming carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

Mr. Trump’s order comes after years of delays at the I.S.A. in setting up a regulatory framework for seabed mining. The authority still has not agreed to a set of rules.

The executive order could pave the way for the Metals Company, a prominent seabed mining company, to receive an expedited permit from NOAA to actively mine for the first time. The publicly traded company, based in Vancouver, British Columbia, disclosed in March that it would ask the Trump administration through a U.S. subsidiary for approval to mine in international waters. The company has already spent more than $500 million doing exploratory work.

“We have a boat that’s production-ready,” said Gerard Barron, the company’s chief executive, in an interview on Thursday. “We have a means of processing the materials in an allied friendly partner nation. We’re just missing the permit to allow us to begin.”

Anticipating that mining would eventually be allowed, companies like his have invested heavily in developing technologies to mine the ocean floors. They include ships with huge claws that would extend down to the seabed, as well as autonomous vehicles attached to gargantuan vacuums that would scour the ocean bottom.

Some analysts questioned the need for a rush toward seabed mining, given that there is currently a glut of nickel and cobalt from traditional mining. In addition, manufacturers of electric-vehicle batteries, one of the main markets for the metals, are moving toward battery designs that rely on other elements.

Nevertheless, projections of future demand for the metals generally remain high. And Mr. Trump’s escalating trade war with China threatens to limit American access to some of these critical minerals, which include rare-earth elements that are also found in trace quantities in the seabed nodules.

The U.S. Geological Survey has estimated that nodules in a single swath of the Eastern Pacific, known as the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, contain more nickel, cobalt and manganese than all terrestrial reserves combined. That area, in the open ocean between Mexico and Hawaii, is about half the size of the continental United States.

The Metals Company’s contract sites are in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, where the ocean is on average about 2.5 miles deep. The company would be the first to apply for an exploitation permit under the 1980 law.

Mr. Barron blamed an “environmental activist takeover” of the I.S.A. for its delays in establishing a rule book that his company could have played by, leading it to apply directly to the U.S. government instead.

In a statement provided to The New York Times last month, a NOAA spokeswoman, Maureen O’Leary, said that the existing process under U.S. law provided for “a thorough environmental impact review, interagency consultations and opportunity for public comment.”

Under the 1994 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, nations have exclusive economic rights over waters 200 nautical miles from their coasts, but international waters are under I.S.A. jurisdiction. Since the Law of the Sea went into effect, the State Department has sent representatives to meetings at the Seabed Authority’s headquarters in Kingston, Jamaica, creating the impression that the United States intended to honor the terms of the treaty, even though the Senate never formally ratified it.

More than 30 countries have called for a delay or moratorium on the start of seabed mining. An array of automakers and tech companies including BMW, Volkswagen, Volvo, Apple, Google and Samsung have pledged not to use seabed minerals. Representative Ed Case of Hawaii in January introduced the American Seabed Protection Act, which would prohibit NOAA from issuing licenses or permits for seafloor mining activities.

I.S.A. negotiators have spent more than a decade drafting the mining rule book, which would cover everything from environmental rules to royalty payments. Despite a pledge to finalize it by this year, negotiators seemed unlikely to meet that deadline.

Nevertheless, other major world powers like China, Russia, India and several European countries — which have generally supported moving quickly to mine in international waters — objected to the Metals Company’s intention to obtain a permit from the U.S. government.

Much of the hesitation to mine the seabed comes from how little it has been studied by scientists. Polymetallic nodules in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, for instance, lie in a cold, still, pitch-black world inhabited by organisms that marine biologists have encountered only on infrequent missions.

“We think about half the species that live in that area are dependent on the nodules for some part of their development,” said Matthew Gianni, a co-founder of the Deep Sea Conservation Coalition.

The ways companies are proposing to mine would essentially destroy those ecosystems, Mr. Gianni said, and the plumes of sediment caused by the mining could spread out over wider areas, smothering others.

The Metals Company, which has conducted its own environmental research for a decade, has said those concerns are overblown. “We believe we have sufficient knowledge to get started and prove we can manage environmental risks,” Mr. Barron said in the news release last month.

Reaching the deep ocean is expensive and technologically complex, not entirely unlike traveling to another planet. “Mankind has only scratched the surface,” said Beth Orcutt, a microbiologist at the Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences. The deep sea covers roughly 70 percent of the Earth.

Disturbing deep-sea ecosystems, remote as they may seem, could have ripple effects far and wide.

“The ecosystems themselves are really important in the major global cycles that allow the ocean to be productive and to create fish and shellfish and feed people,” said Lisa Levin, an oceanographer at Scripps Institution of Oceanography. “And all of those ecosystems are interconnected, so if you destroy one, we still probably don’t even understand what happens to the others in many ways.”

The biggest consequence might be losing entire ecosystems before scientists have a chance to understand them. That would be a loss of the kind of science that can fuel unexpected discoveries, like new drugs or new insights into how life formed on Earth or could form on other planets.

“If we want to mine the deep sea, we have to be willing to give up those ecosystems,” Dr. Levin said.

Eric Lipton contributed reporting.